Let’s learn what the personal interview method is, its advantages, and its disadvantages.

What is the Personal Interview Method?

A personal or face-to-face interview employs a standard structured questionnaire (or interview schedule) to ensure that all respondents are asked questions in the same sequences.

It is a two-way conversation initiated by an interviewer to obtain information from a respondent. The questions, the wording, and the sequence define the structure of the interview, and the interview is conducted face-to-face.

Studies that obtain data by interviewing people are called surveys. If the people interviewed represent a larger population, such studies are called sample surveys.

Thus, a sample survey is a method of gathering primary data based on communication with a representative sample of individuals.

The number of questions and the exact wording of each question incorporated in a questionnaire are identical to all respondents and are specified in advance.

The interviewer merely reads each question to the respondent and usually restrains from providing explanations of the questions if the respondent asks for clarification.

Advantages of Personal Interviews

Flexibility

Flexibility is the major advantage of the interview study. Interviewers can probe for more specific answers and can repeat and clarify a question when the response indicates that the respondents misunderstood the question.

Response rate

The personal interview tends to have a higher response rate than the mail questionnaire.

Illiterate persons can still answer questions in an interview, and others unwilling to spend their time and energy to reply to an impersonal mail questionnaire may be glad to talk.

Nonverbal behavior

The interviewer is personally present to observe nonverbal behavior and to assess the validity of the respondent’s answer directly.

Control over the interview environment

An interviewer can standardize the interview by ensuring that the interview was conducted in privacy, that there was none to influence the respondent, nor that there was anyone to dictate.

He can prescreen to ensure that the correct respondent is replying, and he can set up and control the interviewing condition.

This is in contrast to a mailed study, where the questionnaire may be completed by people other than the respondent himself/herself under drastically different conditions.

The respondent can thus not ‘cheat’ by receiving prompting or answers from others.

Spontaneity

The interviewer can record spontaneous answers. The respondent does not have the chance to retract his or her first answer and write another, while this is possible in the mail questionnaire.

Spontaneous answers are generally more reliable and informative and less normative than answers about which the respondent has had time to think.

Completeness

In a personal interview, the interviewer can ensure that all questions have been answered.

This reduces the chances for item nonresponse, which refers to the collection of incomplete or missing data for one or more (but not all) characteristics of the individuals.

Scope to deal with greater complexity of the questionnaire

A more complex questionnaire can be used in an interview study. A skilled, experienced, and well-trained interviewer can fill in a questionnaire full of skips, arrows, and detailed instructions that even a well-educated respondent would feel hopelessly lost in a mail questionnaire.

Recording of time to conduct an interview.

The interviewer can record the time required to complete the interview. This record can greatly help subsequent surveys prepare a budget, particularly in determining the optimum sample size in terms of cost.

Disadvantages of Personal Interviews

High cost

Interview studies can be extremely costly.

Costs are involved in selecting, training, and supervising interviewers; paying them; and the travel, accommodation, and time required to complete the fieldwork.

Public relations personnel must be paid for their help in many interview studies.

Lack of anonymity

The interview offers less assurance of anonymity than the mail questionnaire study, particularly if the latter includes no follow-up. The interviewer typically knows the respondent’s name and address and sometimes information of all members of the household.

This lack of anonymity is a potential threat to the respondent, particularly if the information is damaging, embarrassing, or otherwise sensitive. This may lead to refusal from the respondent to participate in the interview.

Interviewer bias

The flexibility that is the chief advantage of interviews may be a potential source of the interviewer’s influence and bias.

Although interviewers are instructed to remain objective and avoid communicating personal views, they nevertheless often give cues that may influence respondents’ answers.

Sometimes, the interviewer’s sex, race, social class, age, dress, and physical appearance or accent can influence respondents’ answers.

Prolonged time

Interviews are often lengthy and require the interviewer to travel miles. Further, it is common for the interviewer to make several callbacks before an interview is finally granted.

Interviewing Techniques

Research interviewing is not such an easy task as it might appear at the beginning. Respondents often react more to their feelings about the interviewer than to the content of the questions.

It is also important for the interviewer to ask the question properly, record the responses accurately, probe meaningfully, and motivate unbiasedly.

To achieve these aims, the interviewer must be trained to carry out those procedures that foster a good relationship.

The first goal of an interview is to establish a friendly relationship with the respondent. Three factors help in motivating the respondents to cooperate:

- The respondents must believe that their interaction with the interviewer will be pleasant and satisfying. Whether the interaction will be pleasant and satisfying largely depends on the interpersonal skills of the interviewer.

- The respondents must think that answering the survey is an important and worthwhile use of their time. To ensure this, some explanation of the purpose of the study is necessary. It is the interviewer’s responsibility to ascertain what explanation is needed and to supply it.

- The respondents must have any mental reservations satisfied. This arises when respondents have misconceptions and thus might have reservations about being interviewed. The interviewer’s responsibility is to remove these misconceptions.

The survey research center of the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research provides some guidelines on how the interviewer should approach a respondent (University of Michigan 1969, pp,3.2-3.3):

- Tell the respondent who you are and whom you represent (show your identification card, if needed).

- Check if the respondent is busy or away. If it is obvious that the respondent is busy, give a general introduction, and try to stimulate enough interest to arrange an interview at another time. If the respondent is not at home, keep provision for a revisit.

- Tell the respondent what you are doing in a way that will stimulate his or her interest.

- Tell the respondent how he or she was chosen, emphasizing that he or she was chosen in an impersonal way merely because a crosssection of the population is needed.

- Adapt your positive approach to the situation. Assume that the respondent will not be too busy for an interview. Approach him or her as follows:

I would like to come in and talk to you about this,” rather than saying, “May I come in?” “Should I come later?” or “Do you have time now?” or any other approach that gives the respondent a chance to say “no.”

- Try to establish a good relationship. This is what we call rapport building, meaning a relationship of confidence and understanding between interviewer and respondent.

- Adopt probing whenever necessary. The technique of stimulating respondents more fully and relevantly is termed. The chief function of a probe is to lead the respondent to answer more fully and accurately or at least to provide a minimally acceptable answer. A second function is to structure the respondent’s answer and ensure that all topics of interest to the interviewer are covered and the amount of irrelevant information is reduced. Since a probe presents a great potential for bias, a probe should be neutral and appear as a neutral part of the conversation. Appropriate probes should be specified by the designer of the data collection instruments.

Conditions for Successful Interviews

Three broad conditions must be met to have a successful personal interview: They are

- Availability of needed information from the respondent;

- An understanding of the interviewer’s role by the respondent, and

- Adequate motivation by the respondent to cooperate.

Motivation, in particular, is a task for the interviewer. Good rapport with the respondent should be quickly established, and the technical process of collecting data should begin.

The latter often calls for skillful probing to supplement the answers volunteered by the respondent. In addition to these precautions, a few more strategies must be followed for a successful interview.

Ask questions as worded.

Questions must be read as worded.

Also, every respondent should be asked the same questions in the same manner. This is needed to ensure a comparison of answers from all respondents and facilitate the comparison of summary statistics.

Ask questions in order.

While a questionnaire is constructed, due attention is given to the ordering of the questions. It is, therefore, essential that the order of questioning the respondent must be maintained.

It is particularly important when a questionnaire has frequent skips and contingency questions.

Avoid leading the respondents.

If the questionnaire is well constructed and pre-tested (as it should be), it becomes easier for the interviewer to avoid guiding the respondents by asking leading questions.

A leading question is one, by its content, structure, or wording, that leads the respondents toward a certain answer.

An example of such a question is, “Smoking is harmful, isn’t it?” The answer is most likely to be “Yes.”

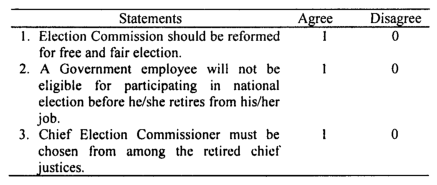

Likewise, the question, “Do you agree that the Health Officer should visit Health Complex every month?” hardly leaves room for “No” or for other options and thus is a leading question.

Reading the questions stated in the questionnaire thus will help the interviewer guard against biasing or leading.

Do not be in a hurry to complete the interview.

A slow pace helps interviewers to enunciate more clearly and allows respondents time to understand the question and formulate an answer.

Ask every question specified in the questionnaire.

Sometimes respondents provide answers to questions before they are asked. When this occurs, the interviewer should still ask the question at the appropriate time while acknowledging the respondent’s earlier answer.

Repeat the misunderstood or misinterpreted questions

Occasionally, language or hearing problems will have difficulties understanding a question. The interviewer should then repeat or reword the question to make it understandable to the respondents.

Dealing with Interview Problems

In personal interviewing, the most important problem is a varying degree of bias that distorts the collected data. Biased results stem from two types of errors: sampling error and non-sampling error. We present a brief overview of these errors below:

Sampling error

The sampling error is always assessed regarding the value of the population parameter.

Whatever may be the degree of cautiousness in selecting a sample from a population, there will always be a difference between the population value and its corresponding estimates.

This difference is attributable to sampling and is referred to as sampling error. Thus the error, which arises entirely due to sampling and no other reasons can be attributed to causing such error, is called sampling error.

Non-Sampling error

In sampling theory, it is implicitly assumed that any observation made on the population takes a unique value whenever the observation is included in the sample, irrespective of the person who collects it.

By implication, we assume that all the selected observations, more precisely the units, can be measured, questioned, or interviewed. All these measurements reveal the true value of any variable of interest.

In practice, however, the situation is seldom so simple, despite our all-out efforts. An example can well illustrate the situation.

Consider a market research team interviewing selected customers at shopping malls in a city to estimate how many of them would buy a new product displayed and demonstrated on-site.

We may reasonably argue that not all buyers do their shopping in the malls; thus, the population of all buyers and buyers in the malls is not identical.

Further, some of the selected buyers could be in a hurry and thus may skip being questioned.

Some might not be interested in participating in the demonstration. Even if they participate, their responses may differ from their real intentions.

These untrue responses could be attributed to a variety of reasons: their misunderstanding of the quality of the product, their price or a lack of attention at the demonstration, and many others.

For all these reasons, the resulting estimates, say the proportion of buyers who would buy the product, could be misleading, even if the sample is technically well designed. The estimators used here have desirable long-term properties (Tryfos, 1996).

The survey scenario, just described above, is a realistic description of a sample survey that demonstrates the potential sources of errors that differ from sampling errors. These errors are called non-sampling errors.

In practice, every survey operation is a potential source of nonsampling errors.

These errors result from mistakes in implementing data collection and processing, such as failure to locate and interview the correct household, misunderstanding of the questions on the part of either the respondent or the interviewer, and data entry errors.

While this suggests a multiplicity of sources of non-sampling errors, we can group them into two broad categories as follows:

- Non-response errors

- Measurement errors

Non-response error

In surveys, it frequently happens that selected persons remain absent or are unwilling to be questioned.

Even when the person is willing to respond, he or she may not answer the question truthfully, intentionally, or not. The survey data thus encounter the problem of non-response and inaccurate response.

There may be two kinds of non-response: element non-response and item non-response.

Element non-response refers to the situation when no data can be collected for one or more of the elements selected for the survey. An element may be an individual (respondent) or any other unit, such as a household.

The reasons for such non-response may be either because;

- the respondents could not be contacted,

- they could be contacted, but they refused to be interviewed or that

- they were contacted and provided data, but the elicited data were dubious in quality and thus were excluded from data processing.

Item non-response refers to the collection of incomplete or missing data for one or more (but not all) characteristics of the individuals.

These stem largely from

- refusal on the part of the respondents. This happens in such cases as properties, incomes, and addiction, for which many respondents are unwilling to cooperate.

- The collected data on the item is of poor quality, making it necessary to discard them from the subsequent analysis.

For obvious reasons, non-response rates vary greatly between surveys. The household non-response rate in the 1976 Bangladesh Fertility Survey (BFS) was 4.7%, while this rate was computed to be 2.4% for the individual interview.

In 1989 BFS surveys, these rates were 4.2% and 1.6%, respectively. In contrast to these surveys, 1993-1994 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Surveys (BDHS), the household and individual interview nonresponse rates were 0.1 % and 2.6%, respectively.

The principal reason for non-response in 1993-1994 BDHS among the respondents was a failure to find them at home despite repeated visits to the household.

For this reason, the 1976 BFS survey accounted for 56.1% of the total cases. The next important reason for non-response was refusal, contributing 22.8% to the total non-response. In 1989 CPS, the overall non-response rate for the household interview was 6.5%, of which about 50% accounted for the reason “dwelling vacant.”

Non-response rate for “address not found” and “address not exists” was also significant (1.44%). In contrast to the household interview, the individual interview showed a non-response rate of only 3 percent, half of the household survey.

Non-response rates are relatively more pronounced in;

- mail surveys,

- surveys dealing with sensitive issues, and

- interview surveys with inadequately trained interviewers.

How to deal with non-response?

One obvious answer is that non-response can be kept at a minimum by repeated visits. In some studies, it is possible to elicit responses from non-respondents by contacting them a second time, appealing to their sense of duty and responsibility.

If all the first-time respondents now respond truthfully, the problem is over. Any estimator, mean, or proportion based on the responses received will become unbiased.

In many instances, the non-response still exits despite several rounds of visits. In 1989 CPS, the interviewers made as many as four visits to a respondent before classifying the case as a non-response (CPS Final Report, 1989).

It is, however, obvious that additional contacts are timeconsuming, add to the cost of sampling, and increase the chance of distorted response.

There will always remain some persons who will not respond to any reasonable inducement. Practical considerations, therefore, usually limit the number of re-contacts, and after all appeals are exhausted, there are likely to be some who have not responded.

The preceding discussions reveal is that there can be no neat solution to deal with the non-response problem without additional assumptions.

An assumption frequently made explicitly or implicitly is that “those who do not respond are similar on average to those who respond.” Whether or not this assumption is reasonable must be judged in each case.

An alternative way to deal with the problem is to eliminate the nonresponse by making it compulsory to cooperate. This may, however, result in untruthful responses to the questions when forced to cooperate. As a result, data may suffer from response bias.

Since non-response can hardly be avoided, we will attempt to achieve a low non-response rate as possible. Here are some measures that are likely to contribute to achieving a low non-response rate:

- Making the audience survey oriented

- Imparting training to the survey statisticians

- Imparting adequate training to the survey interviewers

- Callbacks and reminders

- Sub-sampling the non-respondents.

If people have a positive attitude and appreciation of statistics, they will likely cooperate to a larger extent, thereby contributing to the response rate.

A good understanding of the consequence of non-response by the statistician also contributes to this end. Experience of various surveys has demonstrated that adequate training of interviewers prepares them to tackle the problem of non-response to a considerable extent.

In an interview survey, likely, a respondent may not be at home when an interviewer pays a visit to him. Given this, it is desirable and efficient to make revisit him.

With a mail questionnaire survey, those who do not respond to the initial mailing may be sent a reminder with a new questionnaire.

Measurement error

By measurement, we understand determining the ‘true’ value of a variable or category of an attribute of interest.

If we fail to do so, we encounter measurement errors. This simply says that a measurement error occurs when the reported data differs from the actual data. Measurement error is also referred to as response error.

The potential sources of measurement errors, among others, are

- Failure to understand the questions by the respondents;

- The respondents are unaware of the true answers to the question;

- The questions are based;

Think of a survey where a respondent is asked: What is your income?

The question is simple, but most respondents will be simply confused with the question.

Among the problems he encounters in responding are;

- is it household income?

- does it mean monthly or annual, or weekly income?

- is it last month’s income?

Last year’s income? It is also a fact that many people are secretive about disclosing their income for a variety of reasons. The question is so ambiguous that it makes the respondents bored, impatient, and irritated. Thus, several obvious reasons stand in the way of extracting the ‘true’ value of income.

A common feature in age reporting in demographic data collection is that people report their ages ending in certain preferred digits such as 0 and 5.

For example, a person aged 29 or 31 will tend to report his age at 30. This abruptly produces a serious heaping at age 30. Many people also exaggerate their ages to get old-age prestige, particularly when he is pretty old.

Questions that invite respondents to recall a past event may also be answered inaccurately because of memory failure. “At what age did your father die” may be difficult to answer if it occurred at a distance past.

Long questionnaires and interviews make both the respondent and the interviewer bored and impatient, and as a result, they will be in a hurry, thus leading to inaccurate answers.

The wording and contents of the questionnaire thus appear to be an important component in managing non-response errors. However, before we close the discussion on this, we present an overview of what a randomized response refers to in connection with asking sensitive or embarrassing questions.

In many cultures, people do not provide a true response or altogether refuse to respond because of their sensitivity to the question asked.

Imagine a survey designed to estimate the proportion of persons who view X-rated videos, are addicted to marijuana, indulge in immoral activities, have committed a crime, or ever have evaded taxes.

A person, who does not view an X-rated video, say, will most probably respond with a ‘No.’ A viewer’s response, however, could be ‘Yes’ or ‘No,’ or outright refusal to the question. This is true for other cases as well. Thus, direct questioning of these cases may introduce bias in the results.

A reasonable precaution is to treat the responses of the individuals confidentially and assure them that the response cannot be traced back to the respondents.

Such assurances can be given when personal interviews or a mail questionnaire collect the data, but not by any means where the person interviewed may feel alarmed, embarrassed, or afraid of revealing the truth to the interviewer.

A randomized response method has been developed to address this evasive bias problem. The objective is to encourage truthful answers while fully preserving confidentiality. The method aims at encouraging truthful responses by disassociating the question from the response.

Errors can be made at the processing and tabulating stages too. The interviewer’s error is also a potential source of response error. From the introduction to the interview’s conclusion, there are many avenues where the interviewer’s control of the process can affect the data quality.

Ultimately the success of the interview depends on the interviewer’s qualities.