Negotiation is a give-and-take bargaining process that, when conducted well, leaves all parties feeling good about the result and commitment to achieving.

What is Negotiation?

Negotiation implies the involvement of at least two parties. All parties must share some common need or else they would not come together initially.

They must also have needs that they do not share with other parties. Each of them is seen as controlling some resource, which the other desires. They want to reach an agreement on the mutual exchange of resources.

In other words, when parties are not working together to reach an agreement, negotiation does not take place.

The process of negotiation in a conflict situation helps in building on common interests and reducing differences in order to arrive at an agreement. The parties cooperate by getting

together and then try to reduce the conflict of different interests.

Negotiation is an option for conflict resolution when a conflict of interest exists between two or more parties and there is no fixed or established rule that exists to resolve the conflict.

At the same time, the parties prefer to search for agreement rather than to fight, openly capitulate, break off interaction, or take their dispute to a higher authority level to resolve.

It has typically been conceptualized as a form of decision-making that occurs under conditions of mutual interdependence. Within this framework of interdependence, the respective parties attempt to reach a mutually satisfactory agreement through the pursuit of different strategies such as concessions, promises or threats.

Each party must revise its expectations so that others meet their expectations. Although the concessions may not be equal on both sides, the distance between both parties must be reduced if an agreement is to be reached and a deadlock is avoided.

A negotiation situation is one in which

- Two or more individuals must make a decision about their interdependent goals and objectives;

- The individuals are committed to peaceful means for resolving their disputes and

- There is no clear or established method or procedure for making the decision.

It can be understood that negotiation occurs whenever two or more conflicting parties attempt to resolve their divergent goals by redefining the terms of their interdependence.

Nature of Negotiation

Negotiation is a method by which people settle differences. It is a process by which compromise or agreement is reached while avoiding arguments and disputes.

It is a dialogue between two or more people or parties to reach a beneficial outcome.

This beneficial outcome can be for all of the parties involved or just for one or some of them.

In another way, negotiation is a process in which two or more parties exchange goods or services and attempt to agree on the exchange rate for them.

It is aimed to resolve points of difference, to gain advantage for an individual or collective, or to craft outcomes to satisfy various interests. It is often conducted by putting forward a position and making small concessions to achieve an agreement.

The degree to which the negotiating parties trust each other to implement the negotiated solution is a major factor in determining whether negotiations are successful. Negotiation is not a zero-sum game; if there is no compromise, the negotiations have failed.

When negotiations are at an impasse, it is essential that both parties acknowledge the difficulties and agree to work towards a solution at a later date.

Negotiation is an open process for two parties to find an acceptable solution to a complicated conflict.

There are some specific conditions where negotiation will achieve the best results;

- When the conflict consists of two or more parties or groups.

- A major conflict of interest exists between both parties.

- All parties feel that the negotiation will lead to a better outcome.

- All parties want to work together instead of having a dysfunctional conflict situation.

Elements of Negotiation

There are many different ways to categorize the essential elements of negotiation.

One view of negotiation involves three basic elements:

- Process,

- Behavior, and

- Substance.

The process refers to how the parties negotiate.

The context of the negotiations, the parties to the negotiations, the tactics used by the parties, and the sequence and stages in which all of these play out. Behavior refers to the relationships among these parties, the communication between them, and the styles they adopt.

The substance refers to what the parties negotiate over: the agenda, the issues (positions and – more helpfully – interests), the options, and the agreement(s) reached at the end.

Another view of negotiation comprises 4 elements:

- Strategy,

- Process,

- Tools, and

- Tactics.

The strategy comprises the top level goals – typically including relationship and the final outcome.

Processes and tools include the steps that will be followed and the roles are taken in both preparing for and negotiating with the other parties.

Tactics include more detailed statements and actions and responses to others’ statements and actions.

Some add to this persuasion and influence, asserting that these have become integral to modern day negotiation success, and so should not be omitted.

But according to Members of the Harvard Negotiation Project developed 7 elements of negotiation.

- Interests.

- Legitimacy.

- Relationships.

- Alternatives and BATNA.

- Options.

- Commitments.

- Communication.

Principles of Negotiation

Fisher and Ury (1981), in their excellent book, “Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement without Giving In,” make a very good point that everybody is a negotiator. Whenever we have a conflict with another party, we are required to negotiate.

Negotiation skills are essential for managing interpersonal, intergroup, and intragroup conflicts.

Since managers spend more than one-fifth of their time dealing with conflict, they need to learn how to negotiate effectively.

Sometimes they are required to negotiate with their superiors, subordinates, and peers, and, at other times, they are required to mediate conflict between their subordinates.

Fisher and Ury (1981; see also Fisher, Ury, & Patton, 1993) have forcefully argued that a method called principled/ethical negotiation or negotiation on merits can be used to manage any conflict.

Principled negotiation involves the use of an integrating style of handling conflict. Fisher and Ury’s four principles of negotiation relate to people, interests, options, and criteria as follows:

- Separate the People from the Problem

- Focus on Interests, Not Positions

- Invent Options for Mutual Gain

- Insist on Using Objective Criteria

Separate the People from the Problem

If the parties can concentrate on substantive conflict instead of on affective conflict, they may be able to engage in the problem-solving process. Unfortunately, “emotions typically become entangled with the objective merits of the problem.

Hence, before working on the substantive problem, the ‘people problem’ should be disentangled/separated from it and dealt with separately” (Fisher & Ury, 1981). In other words, the conflicting parties should come to work with and not against each other to deal with their common problem effectively.

Focusing on the problem instead of the other party helps to maintain their relationship.

Hockey and Wilmot (1991) suggest that for parties in interpersonal conflicts, “long-term relational or content goals can become superordinate goals that reduce conflict over short-term goals, but only if you separate the people from the problem.”

Focus on Interests, not Positions

This proposition is designed to overcome the problem of focusing on the stated positions of the parties because the goal of conflict management is to satisfy their interests. A position is what a party wants, that is, a specific solution to an interest.

If a bargainer starts with a position, he or she may overlook many creative alternative solutions for satisfying the interests.

Fisher and Ury (1981) argue, “When you do look behind opposed positions for the motivating interests, you can often find an alternative position that meets not only your interests but theirs as well.” This is especially true in organizations where members are very often concerned about productivity, efficiency, cost, and so on.

Interest defines the problem, not Position.

- Position: Wants the fan ‘on.’

- Interest: Wants fresh air.

- Position: Wants the fan ‘off.’

- Interest: Wants to manage his papers.

Interest and position

- Needs, desires, concerns, and fears behind conflict are interests.

- Interest motivates people to hold a position.

- Position is likely to be concrete and explicit.

- Interests are the silent movers behind certain positions.

Looking to interests instead of positions helps to develop a solution.

- Management’s position: Not to increase wage level.

- Workers’ position: Increase wage level.

- Management’s interest: Survive in the global competitive market with lower production cost.

- Workers’ interest: Meet their basic needs as the cost of living is increasing day by day.

How to identify interests?

- Ask “why?”

- Ask “why not?”

Question Faced: Should I accept the demand of workers?

| If the management says ‘Yes’ | If the management says ‘No’ |

|---|---|

| (-) Production cost Increase | (+) Production cost remains same |

| (-) Lower profit | (+) We have a chance of getting more profit |

| (-) Loss of competitiveness | (+) We can compete effectively in the global market. |

| (-) Management looks weak | (+) We look strong |

| (-) We get nothing | (+) We stand up to the workers. |

| (-) They may perceive us as soft and may come with more demand in the future. | |

| (+) May increase worker satisfaction that may increase productivity. | (-) International organizations may interfere. |

| (+) Helpful to maintain good working relationship | (+) Helpful to maintain a good working relationship |

| (+) Will get international support. | (-) Rivals may use these situations. |

To consider all these interests, different alternative solutions can be taken to resolve conflict.

Invent Options for Mutual Gain

Bargainers rarely see the need for formulating options or alternative solutions so that parties may benefit. As was mentioned before, during a period of intense conflict, the parties may have difficulty in formulating creative solutions to problems that are acceptable to both parties.

It would help if the parties could engage in a brainstorming session designed to generate as many ideas as possible to solve the problem at hand.

Insist on Using Objective Criteria

To manage conflict effectively, a negotiator should insist that results be based on some objective criteria. Brett (1934) presented the classic example of “the tale/story of the mother with two children and with one piece of cake. Because both children are clamoring/crying for the entire piece, the wise mother tells one child he can cut the cake into two pieces and tells the other child she can make the first choice.”

Examples of objective criteria include market value, attainment of specific goals, scientific judgment, ethical standards, and so on.

Once the negotiators start searching for objective standards for managing conflict effectively, the principal emphasis of the negotiation changes from negotiations over positions to alternative standards.

9 Factors Responsible for Making Negotiation Successful

The factors responsible for making the negotiation process successful are;

Effective Communication

Communication is the key to effective negotiation. It requires presenting one’s own ideas in a way that will influence the decision of the negotiating partner.

Communication can be effective if all its elements are used properly and are appropriate to the context. These elements can include body language, words used, and voice tone.

One research finding showed that body language has a 55% impact, voice tone has a 38% impact, and words have a 7% impact on the communication process.

Active listening facilitates the communication process by making the person hear others’ points of view. It involves several components like paying attention, controlling yourself so that you can learn from others, asking open-ended rather than yes-or-no questions, and listening to the answers.

Understanding how to use the power of silence, making sure you are on the same page, and reinforcing the obligation of reciprocity are also important aspects.

Sometimes, one is required to reframe troublesome and confusing sentences. In every discussion, one should ask oneself, “What is the point of this negotiation?” so that one remains focused on one’s BATNA.

Building Relationships

In conflict resolution, it is crucial to maintain relationships even after the negotiation process concludes. Maintaining good business relationships in business-to-business negotiations enhances the company’s reputation and increases the likelihood of repeat business. Issues need to be addressed carefully to avoid jeopardizing the relationship. This is achieved by separating the person from the problem.

Knowing BATNA

BATNA serves as a guideline for negotiations, providing a clear understanding of the negotiation’s goals, available alternatives, and walk-away values.

It offers information to make wise decisions on the negotiation’s substantive elements. BATNA is dynamic in nature because interactions with other parties may lead to changes that facilitate the bargaining process.

Understanding Emotions

The bargaining process becomes easier when one understands the potential emotional issues on the other side. This understanding helps emphasize important points or request additional concessions. On the other hand, maintaining control over emotional expressions, such as the ability to express surprise, significantly impacts negotiations.

Losing control of one’s emotions is a weakness. One should be judicious in expressing emotions. In the bargaining process, it is important to separate the problem from emotional issues to avoid conflicts.

Silence can also be a powerful tool. Instead of reacting strongly to outrageous statements, it is often better to remain silent. However, it should not be used too frequently, as it can lose its effectiveness.

Understanding Interests

In the negotiation process, knowing one’s interests and focusing on them is vital. Cohen has suggested a few questions to uncover one’s interests:

- If my objective is not achieved, will I suffer any damage? If so, what is the damage?

- How does achieving or failing to achieve my objective reflect on my ego, career aspirations, hopes for my family, and the good of my company?

- What alternative routes are available to achieve my underlying goals? Does using an approach different from my announced objective threaten my interests?

- Is my interest as easy to explain to myself or to others as the goal I have chosen?

- How many alternatives are acceptable to me, and why?

Understanding the interests of the negotiation counterparts helps uncover hidden agendas behind their negotiation strategies and objectives, aiding in drawing realistic conclusions. Staying focused on interests helps overcome cultural and other obstacles to agreement and prevents regrettable decisions.

Creative Approach

A creative approach to the negotiation process is essential, making it more interesting. It requires considering the situation from a different perspective. When parties have a win-win orientation, the objective is to find a creative solution that preserves everyone’s initial offer points.

They aim to reach an arrangement where each side loses relatively little value on some issues and gains significantly more on others. Creativity expands the possibilities available to negotiating parties, increasing the likelihood of both sides feeling they have gained from the negotiation.

Fairness

Unless the parties perceive the negotiation process as fair, there is a risk that negotiators will feel less committed to the agreement. Fairness also contributes to a good reputation for the negotiator.

Situational Factors Influence Negotiation

The effectiveness of negotiation depends on situational factors such as location, physical setting, time passage, deadlines, and audience characteristics. Negotiating on one’s own territory is easier because one is familiar with the negotiating environment and can maintain comfortable routines. Sometimes, negotiators prefer neutral territory.

Skilled negotiators generally prefer face-to-face meetings. The physical distance between the parties, the formality of the setting, and seating arrangements can influence their orientation toward each other and the disputed issues.

Time should be allocated for negotiation, but excessive time investment can weaken commitment to reaching an agreement. Time deadlines are essential because they motivate people to complete negotiations, but they can also inhibit effective negotiation.

Negotiators under time pressure process information less effectively. The audience’s knowledge about the negotiation process significantly affects the negotiator.

When the audience has direct surveillance over the proceedings, negotiators tend to take a hard-line approach and place more importance on saving face.

Commitment to Results

Negotiation is a process involving interactions among individuals, intended to result in an agreement and a commitment to a course of action. A negotiation can only be considered successful when it leads to an agreement to which both parties are committed.

Contemporary Negotiation Skills

There are now recognized alternative approaches to traditionally recognized distributed and positional bargaining and the hard versus soft strategies in negotiation.

Whetten and Cameron suggest an integrative approach that takes an “expanding the pie” perspective that uses problem-solving techniques to find win-win outcomes.

Based on a collaborative strategy, the integrative strategy, the integrative approach requires the effective negotiator to use skills such as’

- Establishing superordinate goals,

- Separating the people from the problem,

- Focusing on interests, not on positions,

- Inventing options for mutual gain, and

- Using objective criteria.

Recent practical guidelines for effective negotiations have grouped the techniques into degrees of risk to the user as follows:

Low – risk Negotiation Techniques

- Flattery – subtle flattery usually works best, but the standards may differ by age, gender, and cultural factors.

- Addressing the easy point first — this helps build trust and momentum for the tougher issues.

- Silence – this can be effective in gaining concessions, but one must be careful not to provoke anger or frustration in opponents.

- Inflated opening position – this may elicit a counteroffer that shows the opponent’s position or may shift the point of compromise.

- “Oh, poor me” – this may lead to sympathy but could also bring out the killer instinct in opponents.

High – risk Negotiation Techniques

- Unexpected temper losses – erupting in anger can break an impasse and get one’s point across, but it can also be viewed as immature or manipulative and lead opponents to harden their position.

- High – balling – this is used to gain trust by appearing to give in to the opponent’s position, but when overturned by a higher authority, concessions are gained based on the trust.

- Boulwarism (“take it or leave it”) – named after a former vice president of GE who would make only one offer in labor negotiations, this is a highly aggressive strategy that may also produce anger and frustration in opponents.

- Waiting until the last moment – after using tactics and knowing that a deadline is near, a reasonable but favorable offer is made, leaving the opponent with little choice but to accept (Adler, Rosen, SUverstein, 1996).

Besides these low – high-risk strategies, there are also a number of other negotiation techniques, such as a two-person team using “good cop – bad cop” (one is tough, followed by one who is kind), and various psychological ploys, such as insisting that meetings be held on one’s home turf, scheduling meetings at inconvenient times, or interrupting meetings with phone calls or side meetings.

There are even guidelines of if, when and how to use alcohol in negotiations.

As the president of Saber Enterprises notes, when the Japanese come over to negotiate, it is assumed that you go out to dinner and have several drinks toast with sake.

Because of globalization and the resulting increase of negotiations between parties of different countries, there is emerging research on the dynamics and strategies of negotiations across cultures.

Types of Negotiators

Three basic kinds of negotiators have been identified by researchers involved in The Harvard Negotiation Project. These types of negotiators are;

- Soft Bargainers,

- Hard Bargainers, and

- Principled Bargainers.

Soft Bargainers

- These people see negotiation as too close to competition, so they choose a gentle style of bargaining.

- The offers they make are not in their best interests, they yield to others’ demands, avoid confrontation, and they maintain good relations with fellow negotiators.

- Their perception of others is one of friendship, and their goal is agreement. They do not separate the people from the problem but are -soft on both.

- They avoid contests of wills and will insist on the agreement, offering solutions and easily trusting others and changing their opinions.

Hard Bargainers

- These people use contentious strategies to influence, utilizing phrases such as “this is my final offer” and “take it or leave it.”

- They make threats, are distrustful of others, insist on their position, and apply pressure to negotiate.

- They see others as adversaries and their ultimate goal is a victory. Additionally, they will search for one single answer and insist you agree on it.

- They do not separate the people from the problem (as with soft bargainers), but they are hard on both the people involved and the problem.

Principled Bargainers

- Individuals who bargain this way Seek integrative solutions and do so by sidestepping commitment to specific positions.

- They focus on the problem rather than the intentions, motives, and needs of the people involved.

- They separate the people from the problem, explore interests, avoid bottom lines, and reach results based on standards (which are independent of personal will).

- They base their choices on objective criteria rather than power, pressure, self-interest, or an arbitrary decisional procedure. These criteria may be drawn from moral standards, principles of fairness, professional standards, tradition, and so on.

Researchers from The Harvard Negotiation Project recommend that negotiators explore a number of alternatives to the problems they are facing in order to come to the best overall conclusion/solution, but this is often not the case.

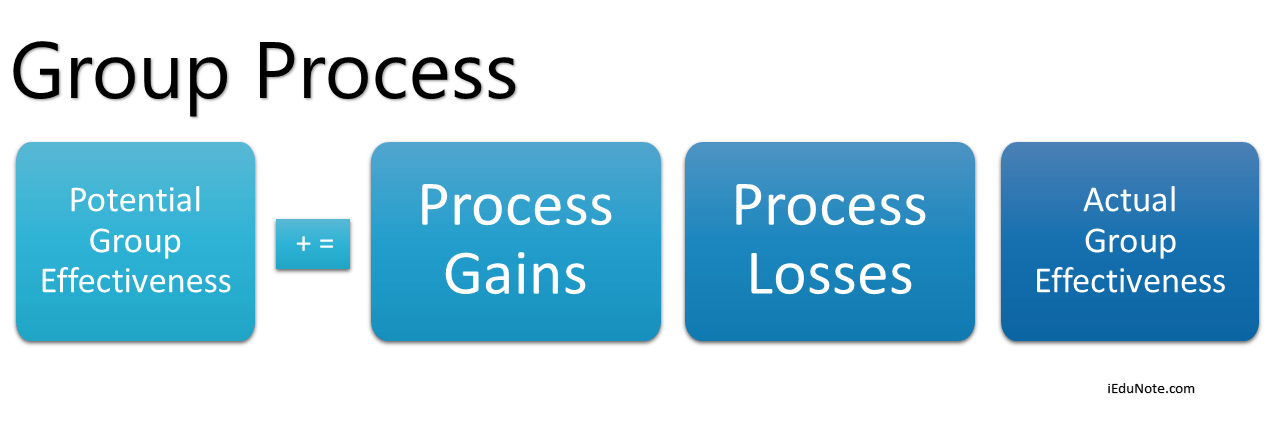

The different types of negotiations, namely distributive, integrative, attitudinal structuring, and intra-organizational, have been discussed in detail as follows.

Distributive Negotiation

It is a competitive negotiation strategy used to decide how to distribute a particular resource, such as money. The parties assume that there is not enough to go around, and they cannot “expand the pie,” so the more one side gets, the less the other side gets.

Since opposing goals, interests, or preferences are at stake, the most effective method of attaining one’s objective is to secure concessions from the other party, although implicitly, one is willing to grant some to the opponent. The bargaining process often results in win-lose outcomes.

The ‘confrontational winner takes all’ approach reflects a misunderstanding of what negotiation is all about and is short-sighted.

Once a confrontational negotiator wins, the other party is not likely to want to deal with that person again. So, the conflict becomes latent and will make one party happy, whereas the other will be dissatisfied. It is also called ‘claiming value,’ ‘zero-sum,’ or ‘win-lose’ bargaining.

Distributive bargaining is important because there are some disputes that cannot be solved in any other way—they are inherently zero-sum. If the stakes are high, such conflicts can be very resistant to resolution.

For example, if a budget in a government agency has to be cut by 30 percent, and people’s jobs are at stake, then a decision about the extent of the cut will be very difficult. If the cuts are so small that the impact on employees will be minor, the effect can be controlled.

In all, disputes arising out of such distributive decisions can be more easily resolved. Labor-management disputes are classic cases of distributive bargaining.

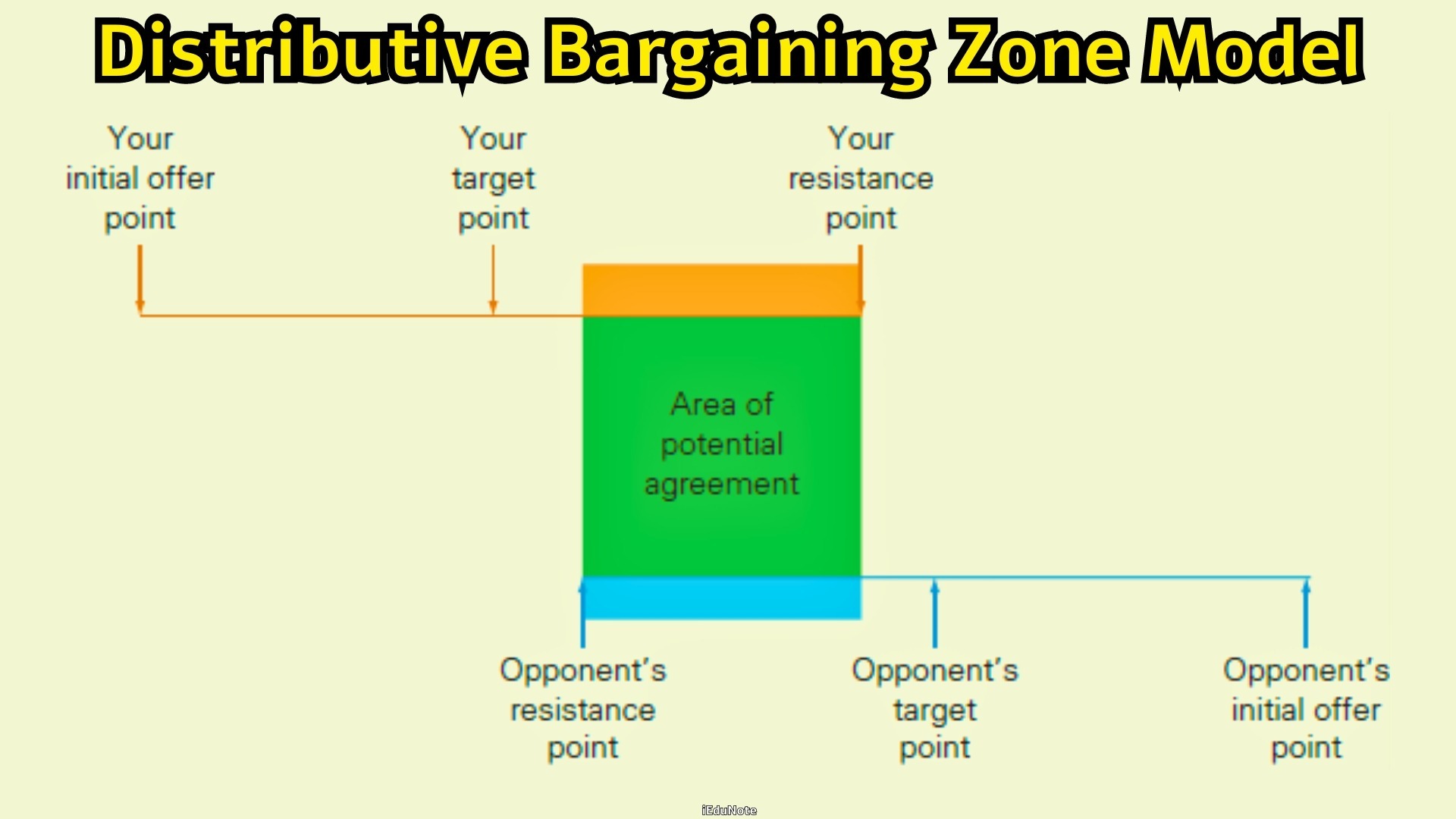

The negotiation process moves each party along a continuum with an area of potential overlap called the bargaining zone. This model illustrates that the parties typically establish three main negotiating points. The initial offer point is the team’s opening offer to the other party.

This is usually its best expectation and a starting point. The target point is the team’s realistic goal or expectation for a final agreement. The resistance point is the point beyond which the team will make no further concessions. This is purely a win-lose situation where one side’s gain will be the other’s loss.

The basic process of distributive bargaining can be explained through the bargaining zone model of negotiations, which is shown in the following figure:

Parties A and B represent two negotiators. Each side has a target point that defines what they would like to achieve and a resistance point that marks the lowest outcome acceptable, i.e., the point below which they would break off negotiations rather than accept a less favorable settlement.

The parties begin their negotiations by describing their initial offer point for each item on the agenda.

In most cases, the participants know that since it is the starting point, it will change as both sides offer concessions. In win-lose situations, neither the target nor the resistance point is revealed to the other party.

However, people try to find out the other side’s resistance point as this knowledge helps them determine how much they can gain without breaking off negotiations.

The trick is to get an idea of the opponent’s walk-away value and then try to negotiate an outcome that is closer to one’s own goals than the other’s. Whether or not parties achieve their goals in distributive bargaining depends on the strategies and tactics they use.

Four of the most common win-lose strategies a negotiator may use are as follows:

- ‘I want it all’—By making an extreme offer and then granting concessions grudgingly, if at all, the negotiator hopes to wear down the opponent’s resolve.

- Time warp—Time can be used as a powerful weapon by the win-lose negotiator. It can be in terms of arbitrary deadlines or offers valid up to a certain period of time, etc.

- Good cop, bad cop—Negotiators using this type of behavior show irrational behavior followed by reasonable, sympathetic behavior.

- Ultimatums—This strategy is designed to try to force the other party to submit to the will of the other party.

Information is the key to gaining a strategic advantage in a distributive negotiation. One should guard one’s own information carefully and also try to gather information about the opponent.

To a large extent, one’s bargaining power depends on how clear one is about one’s goals, alternatives, and target, and resistance point and how much one knows about the opponents.

Once these values are clear, you will be in a much stronger position to figure out when to concede and when to hold firm in order to best influence the response of the other side.

Integrative Negotiation

This is a cooperative approach to negotiation. The negotiators understand the importance of all stakeholders winning something and so try to find out a wide range of interests to be addressed and served. They follow a strategy of collaboration that leads to a “win-win” solution to their dispute. This is known as interest-based negotiation, where the parties focus on their individual interests and the interests of the other parties to find common ground for building a mutually acceptable agreement. They understand that negotiation is not a zero-sum game but a way to create value for all the parties involved. This strategy focuses on developing mutually beneficial agreements based on the interests of the disputants. It helps in building long-term, mutually beneficial relationships.

Negotiation is very much an illustration of joint problem-solving, i.e., each of the parties getting a reasonable share of the pie. Sometimes, the sum available to both parties can be increased by joint effort. If both parties combine to make a larger pie, even though their relative shares (in this case, it is 50:50) remain the same, they both obtain more, which is shown in the following figure.

This is known as a win-win situation. The emphasis here is more on cooperation than on conflict. Integrative bargaining is important because it usually produces more satisfactory outcomes for the parties involved than does positional bargaining. Positional bargaining is based on fixed, opposing viewpoints (positions) and tends to result in compromise or no agreement at all. Often, compromises do not efficiently satisfy the true interests of the disputants. Instead, compromises simply split the difference between the two positions, giving each side half of what they want. Creative integrative solutions, on the other hand, can potentially give everyone most of what they want.

Fisher and Ury outline four key principles for integrative (win-win) negotiations. These principles provide a foundation for an integrative negotiation strategy, which is called “principled negotiation” or “negotiation on the merits.” They are as follows:

- Separate the people from the problem—Negotiators should see themselves as working side by side, dealing with the substantive issues or problems instead of attacking each other.

- Focus on interests, not positions—Focus should be on the underlying human needs and interests that had caused them to adopt those positions.

- Invent options for mutual gain—Varieties of possibilities need to be generated before decisions are made about which action to take.

- Insist on using objective criteria—The parties should discuss the conditions of the negotiation in terms of some fair standard such as market value, expert opinion, custom, or law.

Here we would like to include the complex theory of bargaining model by Fisher et al. as it is no doubt the only proven model, which thus explains disputants and adversaries of distributive and integrative bargaining. Neither distributive bargaining nor integrative bargaining can be overlooked as both sticks to “Getting yes” after a long process of negotiation without giving in. Spangler has simplified the integrative-distributive bargaining process as propagated by Fischer and Ury.

In an integrative negotiation, the parties can combine their interests to create joint value. To achieve integration, negotiators can deal with multiple issues at the same time and make trades between them. In distributive bargaining, in which the participants are trying to divide a “fixed pie,” it is more difficult to find mutually acceptable solutions as both sides want to claim as much of the pie as possible. It is difficult to transform a conflict with distributive potential into one with integrative potential. “In intra-organizational behavior, integrative bargaining is preferable to distributive bargaining because integrative bargaining builds long-term relationships and facilitates working together in the future. Distributive bargaining, on the other hand, leaves one party a loser. It tends to build animosities and deepen divisions when people have to work together on an ongoing basis.”

Attitudinal Structuring

It is the process by which the parties seek to establish desired attitudes and relationships. During the period of negotiation, parties express different attitudes like hostility, competitiveness, or cooperativeness. A third-party mediator can be used to manage the relationship between two parties so that a working relationship can be maintained between them.

Intra-organizational Negotiation

In intra-organizational negotiations, each set of negotiators tries to build consensus for an agreement and resolve intra-group conflict before dealing with the other group’s negotiators. The two groups, before coming to the negotiating table, have to first sort out the issues, attitudes, and practices among themselves. It is necessary for a successful negotiated agreement.

The Role of Personality Traits in Negotiation

Can you predict an opponent’s negotiating tactics if you know something about his or her personality?

It’s tempting to answer Yes to this question.

For instance, you might assume that high-risk takers would be more aggressive bargainers who make fewer concessions. Surprisingly, the evidence doesn’t support this intuition.

Overall assessments of the personality- negotiation relationship finds that personality traits have no significant direct effect on either the bargaining process or the negotiation outcomes. This conclusion is important.

It suggests that you should concentrate on the issues and the situational factors in each bargaining episode and not on your opponent’s personality.

Gender Differences in Negotiation

Do men and women negotiate differently?

And does gender affect negotiation outcomes?

The answer to the first question appears to be No

The answer to the second is a qualified yes (Walters, Stuhlmacher & Meyer, 1999). A popular stereotype held by many is that women are more cooperative and pleasant in negotiations than are men. The evidence doesn’t support this belief.

However, men have been found to negotiate better outcomes than women, although the difference is quite small. It’s been postulated that this difference might be due to men and women placing divergent values on outcomes.

“It is possible that a few hundred dollars more in salary or the comer office is less important to women than forming and maintaining an interpersonal relationship.”

The belief that women are “nicer” than men in negotiations is probably due to confusing gender and the lack of power typically held by women in most large organizations. The research indicates that low-power managers, regardless of gender attempt to placate their opponents and to use softly persuasive tactics rather than direct confrontation and threats.

In situations which women and men have similar power bases, there shouldn’t be any significant differences in their negotiation styles.

The evidence suggests that women’s attitudes toward negotiation and toward themselves as negotiators appear to be quite different from men’s.

Managerial women demonstrate less confidence in anticipation of negotiating and are less satisfied with their performance after the process is complete, even when their performance and the outcomes they achieve are similar to those for men.

This latter conclusion suggests that women may unduly penalize themselves by failing to engage in negotiations when such action would be in their best interests.

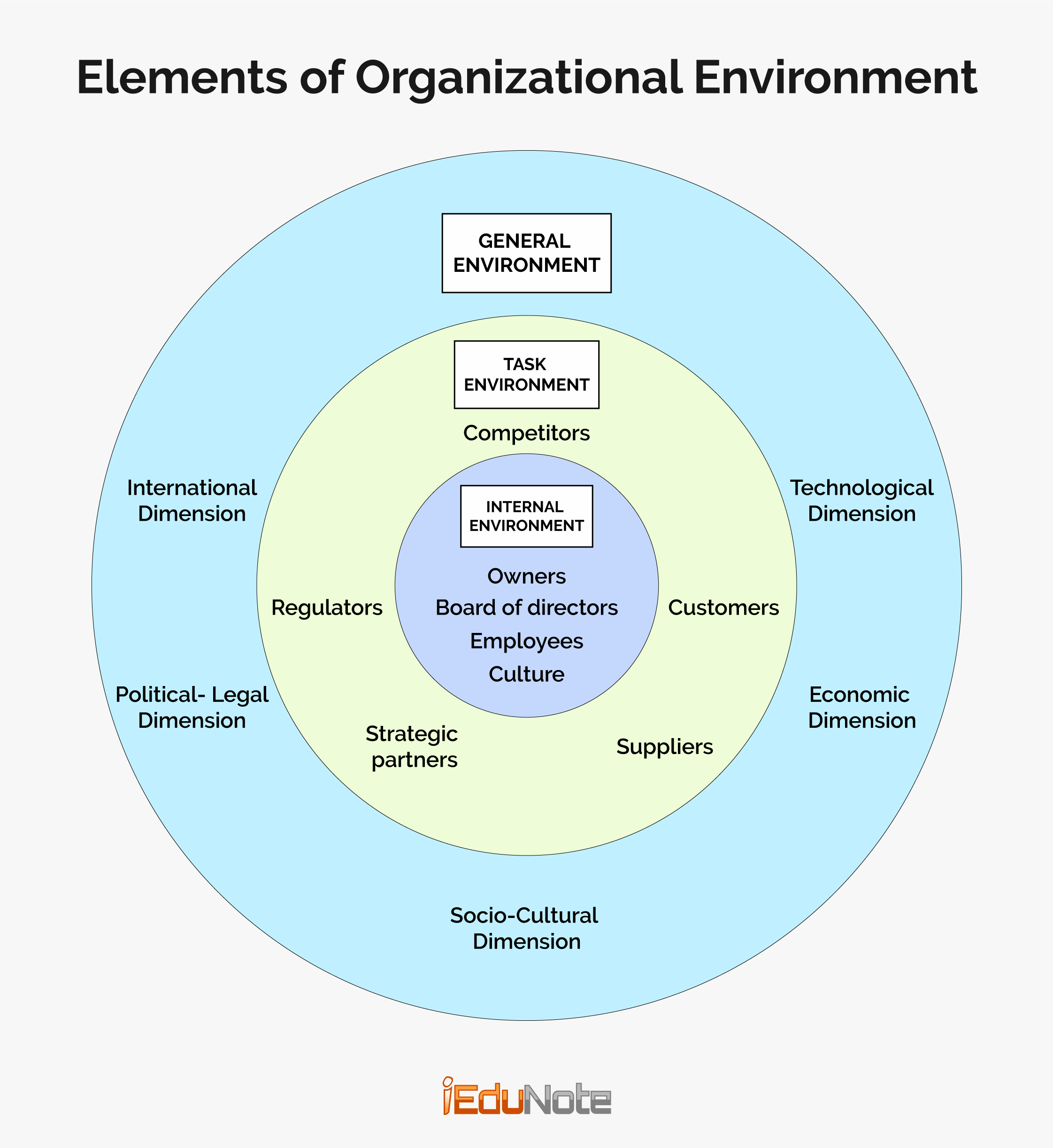

Cultural Differences in Negotiations

Although there appears to be no significant direct relationship between an individual’s personality and negotiation style, the cultural background does seem to be relevant.

Negotiating styles clearly vary across national.

The French like conflict. They frequently gain recognition and develop their reputations by thinking and acting against others. As a result, the French tend to take a long time in negotiating agreements and they aren’t overly concerned about whether their opponents like or dislike them.

The Chinese also draw out negotiations but that’s because they believe negotiations never end. Just when you think you’ve pinned down every detail and reached a final solution with a Chinese executive, that executive might smile and start the process all over again.

Like the Japanese, the Chinese negotiate to develop a relationship and a commitment to work together rather than to tie up every loose end.

Americans are known around the world for their impatience and their desire to be liked.

The cultural context of the negotiation significantly influences the amount and type of preparation for bargaining, the relative emphasis on task versus interpersonal relationships, the tactics used, and even where the negotiation should be conducted.

Third-Party Negotiations

To this point, we’ve discussed bargaining in terms of direct negotiations. Occasionally, however, individuals or group representatives reach a stalemate and are unable to resolve their differences through direct negotiations.

In such cases, they may turn to a third party to help them find a solution. There are four basic third-party roles: mediator, arbitrator, conciliator, and consultant.

Unethical Negotiating Tactics

- Lies

- Puffery (to breathe fast with difficulty)

- Deception/Dishonesty

- Weakening “The Opponent”

- Strengthening “One’s Own Position”

- Information “Exploitation”

- Nondisclosure

- Change of “Mind”

- Disturbance

- Maximization