Ethics in social science research is an indispensable normative approach. In recent years, ethical issues have become very vital points for genuine social research. Social research can rarely be acceptable without ensuring ethical attributes.

Scientific research shows the real path in human society, and it explores the unfolded phenomena of any events (Hossain, 2012; 53).

If the research’s outcome is fake and fabricated, and (because its conducting process is intentional) fraudulent, the readers will reject it, and a suspicious attitude will be nurtured toward other genuine research.

All social research involves some ethical issues. This is because the research involves collecting data from people and about people.

Authentic research can guide future generations in determining their decisions, while unethical and falsified research severely creates controversies and distrust in research contribution.

Ethics in social research has to be maintained from inception to conclusion, and it is very important to maintain its integrity as a holistic cluster of research work.

A researcher must remember this: “You are the best of peoples, evolved for mankind, enjoining what is right, forbidding what is wrong, and believing in Allah” (the Quran 3:110). The various aspects of ethical issues in social science research are discussed in the following sections.

Ethics in Social Research

Defining Ethics

Ethics is a code of conduct in pursuing social science research while maintaining moral aptitudes and operational or functional approaches.

Ethics is also known as moral philosophy, which addresses questions about morality, such as concepts like good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, and justice, etc.

The meaning of ethics and its perception varies from one place to another. In some situations, two contrasting ideas may seem ethical, but it is hard to determine which is the right course of action.

‘Ethics’ can be defined as a ‘set of moral principles and rules of conduct’ (Morrow, 2010). Ethics in research relates to applying a system of moral principles to prevent harming or wronging others, to promote the good, to be respectful, and to be fair (Sieber, 1993: 14).

Indeed, there is an ethical dilemma; for example, which is more ethical?

For example, is it right to steal properties from the rich to give to the poor? Is it right to fight in a war in the name of a good cause, even if innocent people are injured and brutally killed?

To solve all these dilemmas, man cannot judge properly. Only the Almighty Allah (SWT) can guide us.

The term ethics clarifies the following aspects, which are shown in the following figure:

3 Ethical Aspects in General Terms

- Morality in all conducts: The study of standards of conduct, moral judgment, and moral philosophy.

- Treatise on moral aspects: A treatise on this study should be performed, and finally

- Code of morals: The system or code of morals of a particular person, religion, group profession, etc.

Ethics consists of the standards of behavior that our society accepts.

For example, some people accept abortion, but many others do not. If being ethical were doing whatever society accepts, one would have to find an agreement on issues that do not, in fact, exist.

Ethics covers two phenomena.

First, ethics refers to well-founded standards of right and wrong that prescribe what humans ought to do, usually in terms of rights, obligations, benefits to society, fairness, or specific virtues.

In other words, ethics refers to those standards that impose reasonable obligations to refrain from unethical activities such as stealing, murder, assaults, slander, and fraud. Ethical standards also include those that embody the virtues of honesty, compassion, and loyalty.

Ethical standards include standards relating to rights, such as the right to life, the right to freedom from injury, and the right to privacy. Such standards are adequate standards of ethics because consistent and well-founded reasons support them.

Secondly, ethics refers to the study and development of one’s ethical standards. As noted above, feelings, laws, and social norms can deviate from what is ethical.

Ethics also clarifies the continuous efforts of studying our own moral beliefs and our moral conduct, as well as striving to ensure that we, and the institutions we help to shape, live up to standards that are reasonable and solidly based.

Origin of Ethics in Social Research

Ethics in research has been developed as a concept in medical science. The key agreement here is the 1974 Declaration of Helsinki. The Nuremberg Code is a former agreement but with many still important notes.

Research in the social sciences presents a different set of issues than those in medical research. The scientific research enterprise is built on a foundation of trust. Scientists trust that the results reported by others are valid.

Society trusts that the results of research reflect an honest attempt by scientists to describe the world accurately and without bias.

But this trust will endure only if the scientific community devotes itself to exemplifying and transmitting the values associated with ethical scientific conduct (National Academy of Sciences, 2009).

There are many ethical issues to be taken into consideration for social research. Sociologists need to be aware of having the responsibility to secure the actual permission and interests of all those involved in the study.

They should not misuse any of the information discovered, and there should be a certain moral responsibility maintained towards the participants. There is a duty to protect the rights of people in the study as well as their privacy and sensitivity.

The confidentiality of those involved in the observation must be carried out, keeping their anonymity and privacy secure. Social scientists from all over the world have encountered difficulties in conducting social research in cross countries that have hostile relations with the superpowers.

In that perspective, informants and researchers may be accused of being spies, and informants/respondents or data providers may be exposed to harm for appearing to sympathize with ‘the enemy’.

Harm may result even if hostile relations develop after the research has been conducted, for instance, military, Criminal Investigation Agency (CIA), Scotland Yard, Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), and so forth.

Other state agencies may particularly endanger the observed (Johnson et al., 2008: 259).

Recently, an important example can be cited that Julian Assange, founder of WikiLeaks, was apprehended by the British government in cooperation with the US government for exposing confidential reports, documents, files, treaties, and secret information worldwide.

Here, exposing information may be useful for other states, but a big question has arisen on the US part. Research ethics in a social science context are dominated by principles and other genuine contributions (Shaw et al., 2009: 912 – 918).

According to the Islamic perspective, two sources of Islamic Law were used;

- The purposes of the Law (maqasid al shari’af) developed starting in the 5th Islamic century as the basis for an Islamic ethical theory and

- Principles of the Law (qawa ‘id alfiqh), as the basis for ethical principles.

The Purposes of the Law: Ethical Theory

For an act to be considered ethical, it must conform to or not violate one of the 5 major purposes of the Law.

The advantage is that one internally consistent legal or ethical theory is applied to various situations.

The 5 purposes aim at protecting (hifdh), preserving (ibqaa), and promoting (tatwiir) of 5 entities that among them cover all aspects of human endeavor. These are:

- Morality/religion, hifdh al ddiirv,

- Life and health, hifdh al nafs,

- Progeny, hifdh al nafs,

- Intellect, hifdh al ‘aql,

- Resources, hifdh al maal.

Epistemological Explanation of Ethical Research

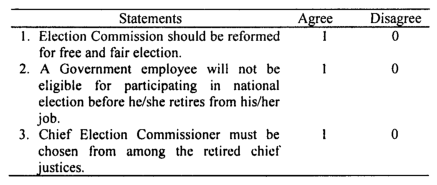

In social research ethical considerations are not always obvious. To overcome this, social scientists have a set of conventions that are held to be true about what is and is not ethical. These conventions cover triadic important relationships which are exposed in the figure beneath.

Triadic bond of ethical relationships

- the researcher-researched relationship

- the researcher-researcher relationship

- the researcher-professional association relationship

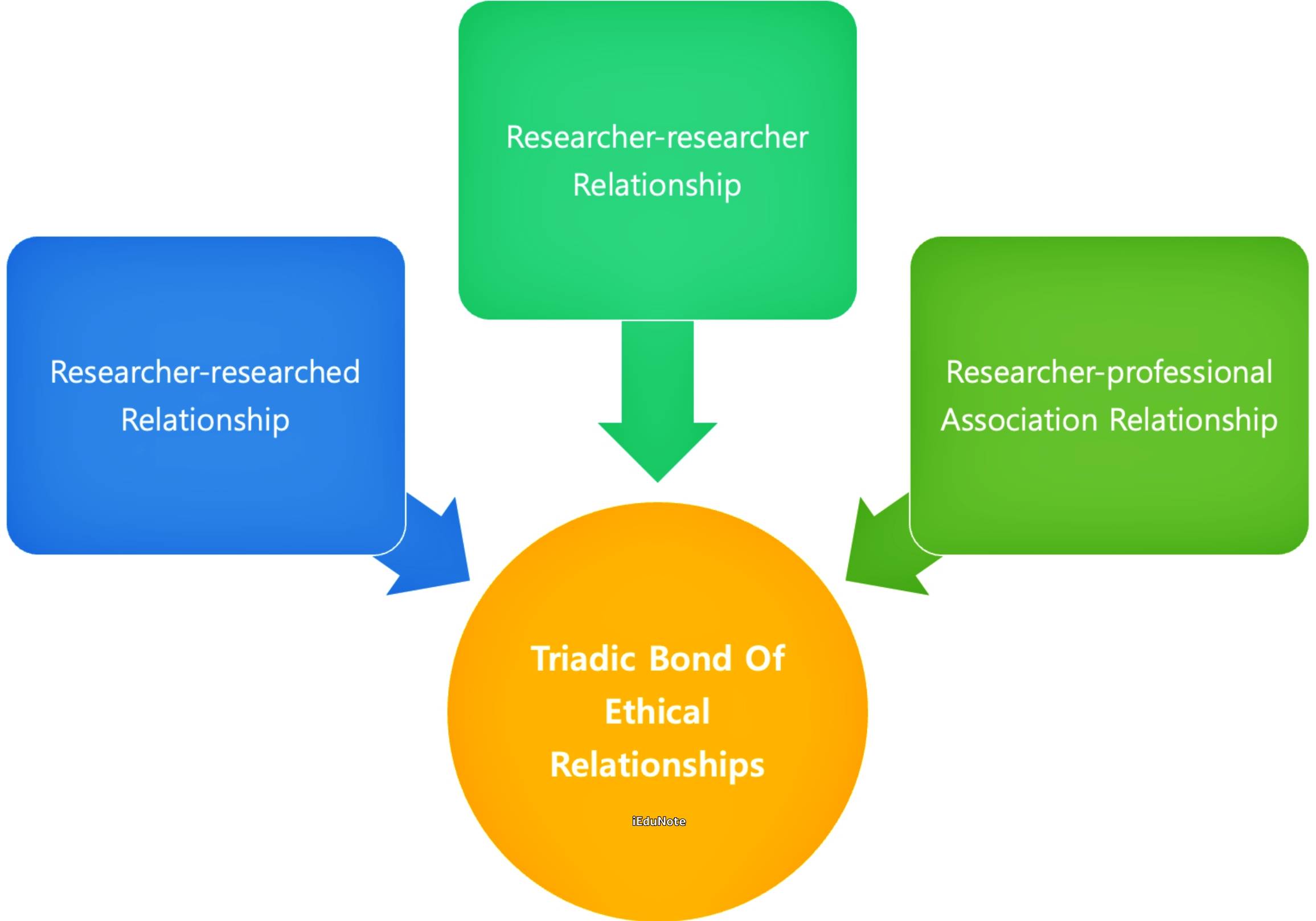

Common Conventional Principles of Ethical Research

Different scientists explained various ethical conventional principles in their perception and understanding that are assumed as the most important common convention in ethical research. These are presented in the following figure for a clear assumption at a glance.

- Not to damage

- Analyzing and reporting data

- Voluntary participation

- Avoiding Decisiveness

- Anonymity and confidentiality

Common Ethical Elements in Social Research

There are a number of key phrases that describe the system of ethical protections that the contemporary social research establishment has created in efforts to protect the rights of their research participants better.

Like all social research, surveys should be carried out to avoid risks to participants, respondents, and interviewers.

The following are some common ethical principles about general populations with which all researchers should be familiar:

Informing Respondents

The researchers should inform the respondents about what data and information they are going to collect. Without maintaining clear transparency about the research purpose to the respondents, collecting data and information is unethical. Islam does not allow the invasion of other people’s privacy.

It is mentioned in the Qur’an: “O you who have believed, do not enter houses other than your own houses until you ascertain welcome and greet their inhabitants. That is best for you; perhaps you will be reminded” (the Qur’an, 24: 27).

Also, the Prophet Muhammad (SAAS) said: “Had I known you were looking (through the hole), I would have pierced your eye with it (comb).”

Then, the order of taking permission to enter has been enjoined because of that sight, (that one should not look unlawfully at the estate of others) (Hadith Al-Bukhari).

Protecting Respondents

Protecting respondents is a common ethical element in social science research. All people who have access to the data or a role in the data collection process should be committed in writing to confidentiality and to protect themselves from the threat of danger.

Ethical standards also require that researchers not put participants in a situation where they might be at ‘risk of harm’ as a result of their participation. From an Islamic perspective, researchers should avoid causing any physical or psychological distress to human beings without a valid reason.

A hadith, which is also a qa’idah fiqhiyyah (Islamic legal maxim), states: “One should not give harm to others or do harmful things to oneself.”

Yusuf Al-Qardawi (1997b) mentioned some actions that can be harmful to others – and thus prohibited. These include relieving oneself in stagnant water, in the shade where people shelter, on the roads, or in reservoirs of water (based on a hadith narrated by Abu Dawud and Ibn Majah, and another hadith narrated by Ahmad and Muslim).

Al-Qardawi also mentioned some other actions, such as the need to cover the vessel (if it contains food or drink) and water skins, the need to close the doors, and the need to extinguish the lamps (at night before sleep) (based on a hadith narrated by Muslim and Ibn Majah).

All these pieces of evidence show Islam’s emphasis on avoiding physical or psychological stress on other human beings (Alias).

Benefits to the Respondents

In most surveys, the main benefits to respondents are intrinsic, enjoying the process of the interview or feeling that they have contributed to a worthwhile effort. More direct benefits, such as payment, prizes, and services, are sometimes provided (Fowler, 1987: 135- 38).

Research should always be for the benefit of humanity and should not harm anyone. Here Al-Shatibi might be mentioned. He introduced the concept of the hierarchy of purposes (maqasid) of the Shariah.

The first hierarchy of purpose is al-maqasid al-daruriyyah (necessary purposes), which are necessary to achieve the interest of religion and life without which corruption and disorder would prevail.

The second hierarchy of purpose is hajiyyal (exigencies) which is intended to ease hardship and difficulties and eliminate negative behavior. The third one is tahsinat (facilities) which is intended to reinforce, uplift, and promote the positive in the life of man. (Yusof, 2009: 4)

Voluntary Respondents

The elements of voluntary participation require that people not be coerced into participating in social science or any other research.

This is especially relevant where researchers had previously relied on ‘captive audiences’ for their subjects, such as prisons and universities, etc. Closely related to the notion of voluntary participation is the requirement of informed consent.

Right to Service

Increasingly, researchers have had to deal with the ethical issue of a person’s right to service. Good research practice often requires the use of a ‘no-treatment control group’.

Even when clear ethical standards and principles exist, there will be times when the need to do accurate research runs up against the rights of potential participants. No set of standards can possibly anticipate every ethical circumstance.

Furthermore, there needs to be a procedure that assures that researchers will consider all relevant ethical issues in formulating their research plans and design.

In addition, scientists are concerned with protecting human rights and establishing safety and security while researching any phenomena.

Overt and Covert Research Actions

Covert and overt ethical actions can be defined and considered heroic in light of what appears to be timidity on the part of many social workers to act against perceived moral injustice in their workplaces (Fine and Teram, 2012).

The concepts of multiple institutional logics and embedded agency are used as a means of moderating and contextualizing the concerns social workers might have about acting in either covert or overt ways to address moral injustices and to examine the potential pitfalls and merits of each type of action.

If overt action is not possible or may have the potential to cause more harm to the client, covert actions can be morally justified.

Overt actions are driven by the imagination of better alternatives, or what Aronson and Smith (2010) call ‘expanded entitlements,’ within the logics of the system within which social researchers are embedded.

These actions do not push for radical changes and are not as risky as covert actions that reject and violate current institutional arrangements.

With respect to overt actions, we would add that much of the risk and anxiety related to taking overt actions against perceived injustice is related to moral ambiguity, which is a product of institutional pluralism.

Covert ethical actions are implicitly outside the constitutional framework of the organization and can hardly be defended on this ground.

A proper understanding of these distinctions is a good starting point for encouraging overt actions, which are more likely to lead to organizational change than covert ethical actions, which, despite their benefits for individual clients, tend to mask and smooth organizational inadequacies.

Covert actions are necessary when the perceived injustice cannot be addressed within the institutionalized logics of the organization, multiple as they may be.

These ethical actions are a product of the realization by social researchers that great energy and time are required to change large systems and, most importantly, the potential harm for clients waiting for the system to change.

Austin et al., (2005: 204) have also reported covert ethical actions: a psychologist in their study felt compelled to act ‘secretly’ to ensure proper treatment for a patient who was becoming increasingly at risk regarding his own safety and mental well-being in the institution.

After a number of pleas to other professionals within the institution, the psychologist realized that inter-institutional politics were preventing a necessary transfer to an appropriate facility (Fine and Teram, 2012).

Overt or Covert Research Observations

A third way to characterize observation is by noting whether it is overt or covert ethical attempt. In overt observation, those being observed are aware of the investigator’s presence and intentions.

In covert observation, the investigator’s presence is hidden or undisclosed, and his or her intentions are disguised. For instance, observation was used in a study to measure what percentage of people washed their hands after using the restroom.

As many healthcare physiologists or general practitioners argued and alerted that the key source of the dyspepsia disease is not using toilet soap required water after using the toilet each time. Most people are reluctant to wash their hands with soap or washing liquid properly.

They should use sufficient washing liquid in their hands to wash them properly after being washed their stomach each time. Research involving covert observation of public behaviors of private individuals is not likely to raise ethical issues as long as individuals cannot be identified.

Covert ethical actions can work to right a particular wrong, but we agree that they do not change systems. Indeed, covert actions can reinforce systems and the status quo, allowing things to run smoothly by not requiring the system to deal openly with its ambiguities (Lipsky, 1984; Hoggett, 2006).

As for overt actions, we believe, as already suggested, that they should occur ideally whenever possible.

Ethical Explanation and its Importance in Social Science Research

Many different disciplines, institutions, and professions have norms for behavior that suit their particular aims and goals. These norms also help members of the discipline coordinate their actions and establish the public’s trust in the discipline.

For instance, ethical norms govern conduct in medicine, law, engineering, and business. Ethical norms also serve the aims and goals of research and apply to people who conduct scientific research or other scholarly or creative activities.

There is even a specialized discipline, research ethics, which studies these norms. There are several reasons (see figure and explanation below) why ethical norms are important in social research, and these are as follows:

Accountable to the Public

Accountability (muhasabah) is the self-control that allows one to judge their deeds. “Then guard yourselves against a Day when one soul shall not avail another….” (2: 123).

First of all, an administrator should remember that they are accountable to Allah (SWT). Then they are accountable to others. Many of the ethical norms help ensure that researchers can be held accountable to the public.

For instance, federal policies on research misconduct, conflicts of interest, human subjects’ protections, and animal care and use are necessary to make sure that researchers funded by public money can be held accountable to the public.

Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) said, “Surely all of you are responsible and will be questioned about their responsibilities.” (Sahih al-Bukhari)

Promote Societal Values and Rights

Since research often involves a great deal of cooperation and coordination among many different people in different disciplines and institutions, ethical standards promote the values essential to collaborative work, such as trust, accountability, mutual respect, and fairness.

Many ethical norms in social research, such as guidelines for authorship, copyright and patenting policies, data sharing policies, and confidentiality rules in peer review, are designed to protect intellectual property interests while encouraging collaboration.

Most researchers want to receive credit for their contributions and do not want to have their ideas stolen or disclosed prematurely.

A Muslim researcher has to follow Islamic manners. For instance, when research is conducted on a one-to-one basis, the experimenter and the participant should belong to the same gender.

When different genders have to work together, a third person should be present, or the experiment should be conducted in a room with a glass door or window so that they are visible from outside. The rights of female participants in respect of their privacy should be particularly respected and protected. (Hussain, 2009)

Invent New Knowledge

Ethical norms promote the aims of research and contribute to new knowledge, truth, and avoidance of error. For example, prohibitions against fabricating, falsifying, or misrepresenting research data promote the truth and avoid error.

As our Prophet Muhammad (SAAS) guides us, “Whosoever introduces a good practice in Islam, there is for him its reward and reward of those who act upon it after him without anything being diminished from their rewards. And whosoever introduces an evil practice in Islam, will shoulder its sin and sins of those who will act upon it, without diminishing in any way their burden.” (Muslim)

Create Public Support

Ethical norms in research also help build public support for research. Most people are more likely to fund a research project if they can trust the quality and integrity of the research. The Islamic way of (waqf) funding may be raised to conduct any valuable research.

Extend Moral Values

Many of the norms of research promote a variety of other important moral values, such as social responsibility, human rights, and animal welfare, compliance with the law, and health and safety. Ethical lapses in research can significantly harm human and animal subjects, students, and the public.

For example, a researcher who fabricates data in a clinical trial may harm or even kill patients, and a researcher who fails to abide by regulations and guidelines relating to radiation or biological safety may jeopardize their health and safety or the health and safety of staff and students.

Prophet Muhammad (SAAS) advised that, ‘Judge each matter by its disposition. If you see good in its outcome, carry on with it: but if you fear transgressing the limits set by Allah, then abstain from it.’ (A Day with the Prophet, No. 114 mentioned in Denffer: 83)