Conflict is a natural disagreement resulting from individuals or groups that differ in attitudes, beliefs, values, or needs. It can also originate from past rivalries and personality differences.

To speak broadly, conflict analysis is a practical process of examining and understanding the reality of the conflict from a variety of perspectives. This understanding then forms the basis on which strategies can be developed and actions planned.

Tools for Conflict Analysis

The different tools used for conflict analysis are as follows:

- The ABC Triangle

- The Onion

- The Conflict Tree

The ABC Triangle

The ABC triangle is a graphic tool, using the image of a triangle. This analysis is based on the premise that conflicts have three major components:

- the context or solution,

- the behavior of those involved, and

- their attitude.

Purposes

- To identify these sets of factors for each of the major parties,

- To analyze how these influence each other.

- To relate these to the needs and fears of each party.

- To identify a starting point for intervention in the situation.

How to use these tools

- Draw up a separate ABC triangle for each of the major parties.

- On each triangle list attitude, behavior and context of each party.

- Indicate the most important needs and fears in the middle of the triangle.

- Compare the triangles.

Labor group

To prepare a triangle for the labor group the analyst must need to know the answers or opinions of five questions.

- Labor view of owners (Behaviors)

- Labor view of themselves (Behaviors)

- Labor view of owners (Attitudes)

- Labor view of themselves (Attitudes)

- Context

Here is an example of the ABC triangle of the labor group.

| Behaviors | |

| Labor view of owner | Labor view of themselves |

| Absorbent | Put best effort |

| Selfish | Hard worker |

| Neglectful | Well wisher |

| Autocratic | Deprived |

| Attitudes | |

| Labor view of owner | Labor view of themselves |

| No tendency to solve conflict | Main contributor |

| Think they are right | Honest and hard worker |

| Neglect labor right | Cheapest labor |

| Context | |

| Insecurity at work place | |

| No trade union | |

| Irregular wages | |

| No labor-oriented industrial relations |

Owner group

To prepare a triangle for owner group, the analyst must need to know the answers or opinion of five questions.

- Owner view of labor (Behaviors)

- Owner view of themselves (Behaviors)

- Owner view of labor (Attitudes)

- Owner view of themselves (Attitudes)

- Context

| Behaviors | |

| Owner view of labor | Owner view of themselves |

| Get beyond deserve | Cooperative |

| No communication Knowledge | Open Mind |

| Negligible | Concern about human rights |

| Attitudes | |

| Owner view of labor | Owner view of themselves |

| Shacking is not expectable | provide perks and privileges |

| Not well wisher | labor erupt is not acceptable |

| consider success of the organization | |

| context | |

| Receives the highest amount of cash incentives. | |

| Keeps production costs at the minimum level by paying low wages. | |

| Focuses on personal benefits. |

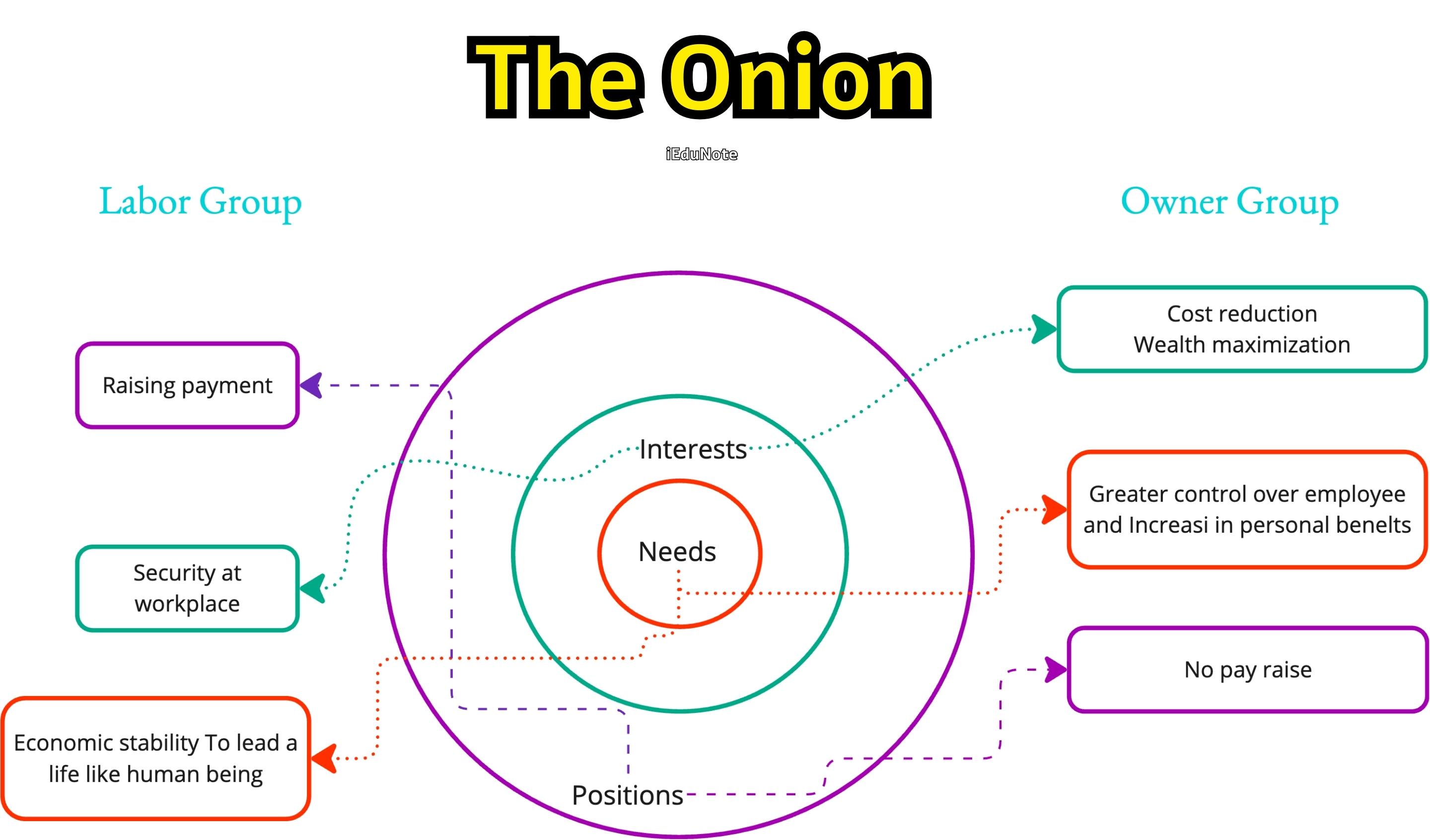

The Onion

The Onion is a graphic tool that uses the image of an onion to analyze what the parties are saying and the reasons behind their statements. It is based on the analogy of an onion and its layers. The outer layer contains the positions that we publicly take for all to see and hear.

Underlying these positions are our interests, which represent what we want to achieve from a particular situation. Finally, at the core, are the most important needs we require to be satisfied.

Purposes:

- To move beyond the public positions of each party and understand each party’s interests and needs.

- To find common ground between the parties that can be used as the basis for further discussion.

This type of analysis is useful for parties who are negotiating to clarify their own needs, interests, and positions. The parties can decide how much of the interior layers, interests, and needs they want to reveal to the other parties.

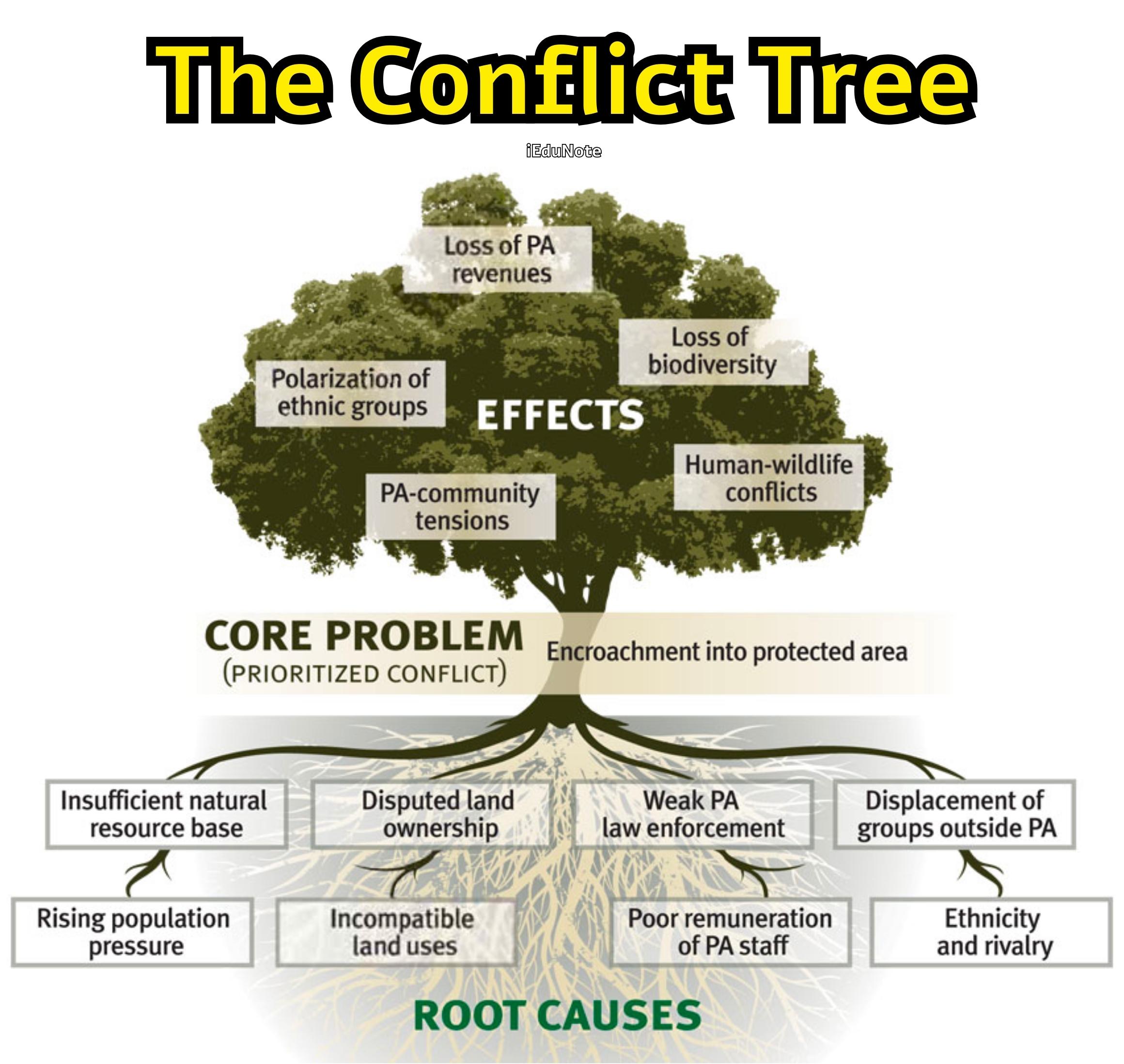

The Conflict Tree

A conflict tree is a graphic tool that uses the image of a tree to sort key conflict issues. This tool is best used within groups, collectively rather than as an individual exercise.

The conflict tree offers a method for a team, organization, group, or community to identify the issues that each of them sees as important and then sort these into three categories:

- Core problem.

- Causes.

- Effects.

Purpose:

- To stimulate discussion about the causes and effects of a conflict.

- To help a group to agree on the core problem.

- To assist a group or a team in making decisions about priorities for addressing conflict issues.

How to use this tool:

- Draw a picture of a tree, including its roots, trunk/chest, and branches.

- Invite people to indicate the key issues in the conflict.

- Invite people to attach their cards to the tree.

- Once all the cards have been placed on the tree, ask people to visualize their own organization as a living entity and place this on the tree.

- After reaching an agreement, people can decide which issues they wish to address.

It’s a long-term process and needs to be continued in future group meetings. Here is an example of a conflict tree:

Guideline for Conflict Analysis through Confrontation

- Agree on the common goal: to solve the problem.

- Commit yourself to fluid, not fixed, positions.

- Clarify the strengths and weaknesses of both parties’ positions.

- Recognize the other person’s, and your own, possible need for face-saving.

- Be candid and up-front; don’t hold back key information.

- Avoid arguing or using “yes-but” responses; maintain control over your emotions.

- Strive to understand the other person’s viewpoint, needs, and bottom line.

- Ask questions to elicit needed information; probe for deeper meanings and support.

- Make sure that both parties have a vested interest in making the outcome succeed.

- Give the other party substantial credit when the conflict is over.

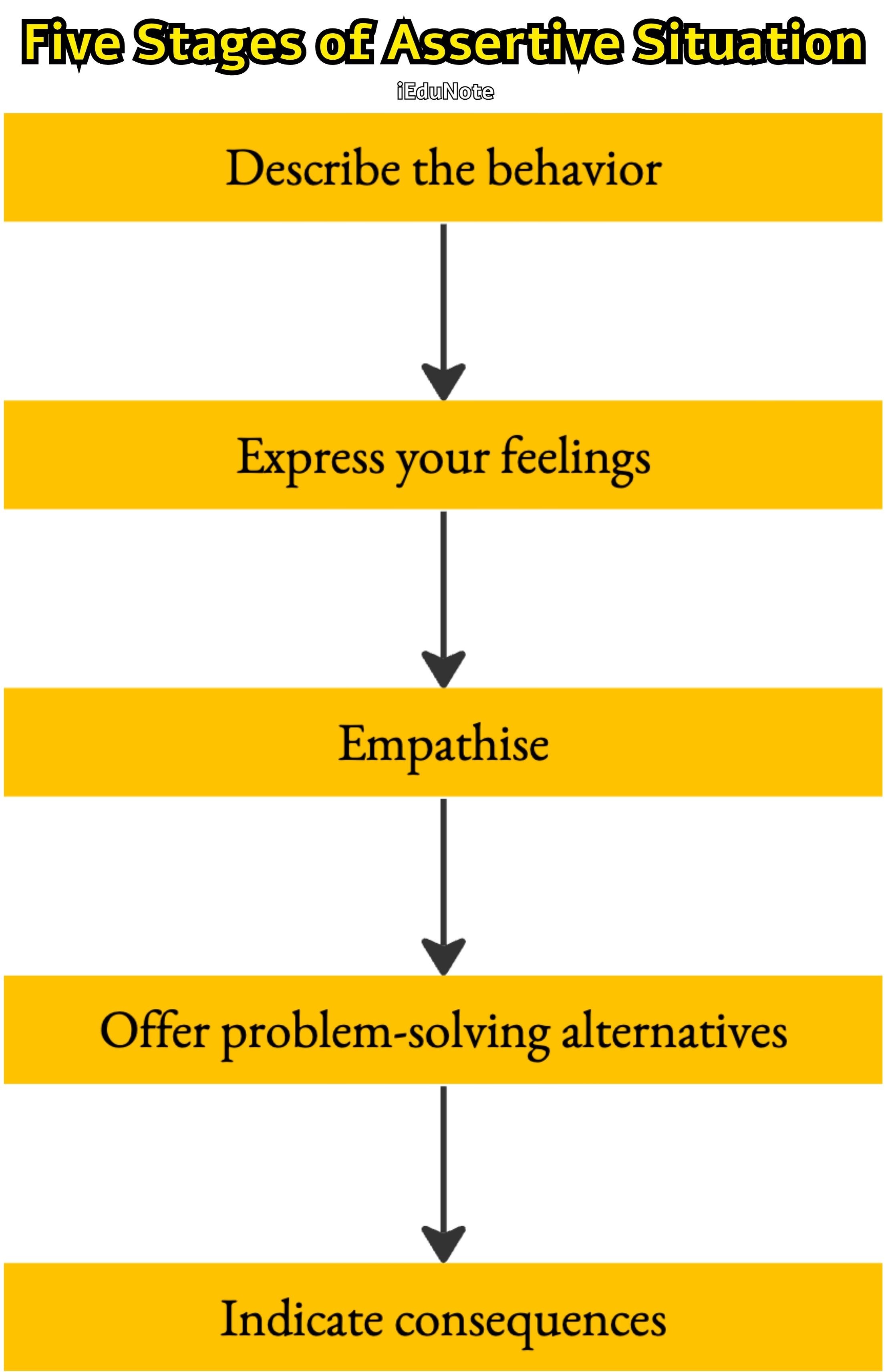

Assertive Behavior

Confronting conflict is not easy for some people. When faced with the need to negotiate with others, some managers may feel inferior, lack the necessary skills, or be in awe of the person’s power. Under these conditions, they are likely to suppress their feelings (part of the avoidance strategy) or to strike out in unintended anger. Neither response is truly productive.

A constructive alternative is to practice assertive behaviors. Assertiveness is the process of expressing feelings, asking for legitimate changes, and giving and receiving honest feedback.

An assertive individual is not afraid to request that another person change an offensive behavior and is not uncomfortable refusing unreasonable requests from someone else.

Assertiveness training involves teaching people to develop effective ways of dealing with a variety of anxiety-producing situations.

Assertive people are direct, honest, and expressive. They feel confident, gain self-respect, and make others feel valued.

By contrast, aggressive people may humiliate others, and unassertive people elicit either pity or scorn from others. Both alternatives to assertiveness typically are less effective for achieving a desired goal.

Being assertive in a situation involves five stages, as shown in the figure. When confronted with an intolerable situation, assertive people describe it objectively, express their emotional reactions and feelings, and empathize with others’ positions.

Then, they offer problem-solving alternatives and indicate the consequences (positive or negative) that will follow. Not all five steps may be necessary in all situations.

As a minimum, it is important to describe the present situation and make recommendations for change. The use of the other steps would depend on the significance of the problem and the relationship between the people involved.

Karla, the supervisor of a small office staff, had a problem. Her secretary, Maureen, had become increasingly careless about her morning arrival time. Not only did Maureen almost never arrive before 8 A.M., but her tardiness varied from a few minutes to nearly half an hour.

Although Karla was reluctant to confront Maureen, she knew she must do so, or the rest of the staff would be unhappy.

Karla called Maureen into her office soon after Maureen arrived the next morning and drew upon her assertiveness training.

“You have been arriving late almost every day for the past two weeks,” she began. “This is unacceptable in an office that prides itself on prompt customer service beginning at 8 A.M. I recognize that there may be legitimate reasons for tardiness on occasion, but I want you to get to work on time most days in the future. If you don’t, I will insert a letter into your personal file and also note your behavior on your six-month performance appraisal. Will you agree to change?”

Assertive behavior is generally most effective when it integrates a number of verbal and nonverbal components. Eye contact is a means of expressing sincerity and self-confidence in many cultures, and an erect body posture and direct body positioning may increase the impact of a message.

Appropriate gestures may be needed, congruent facial expressions are essential, and a strong but modulated voice tone and volume will be convincing. Perhaps the most important is the spontaneous and forceful expression of an honest reaction, such as “Tony, I get angry when you always turn in your report a day late!”

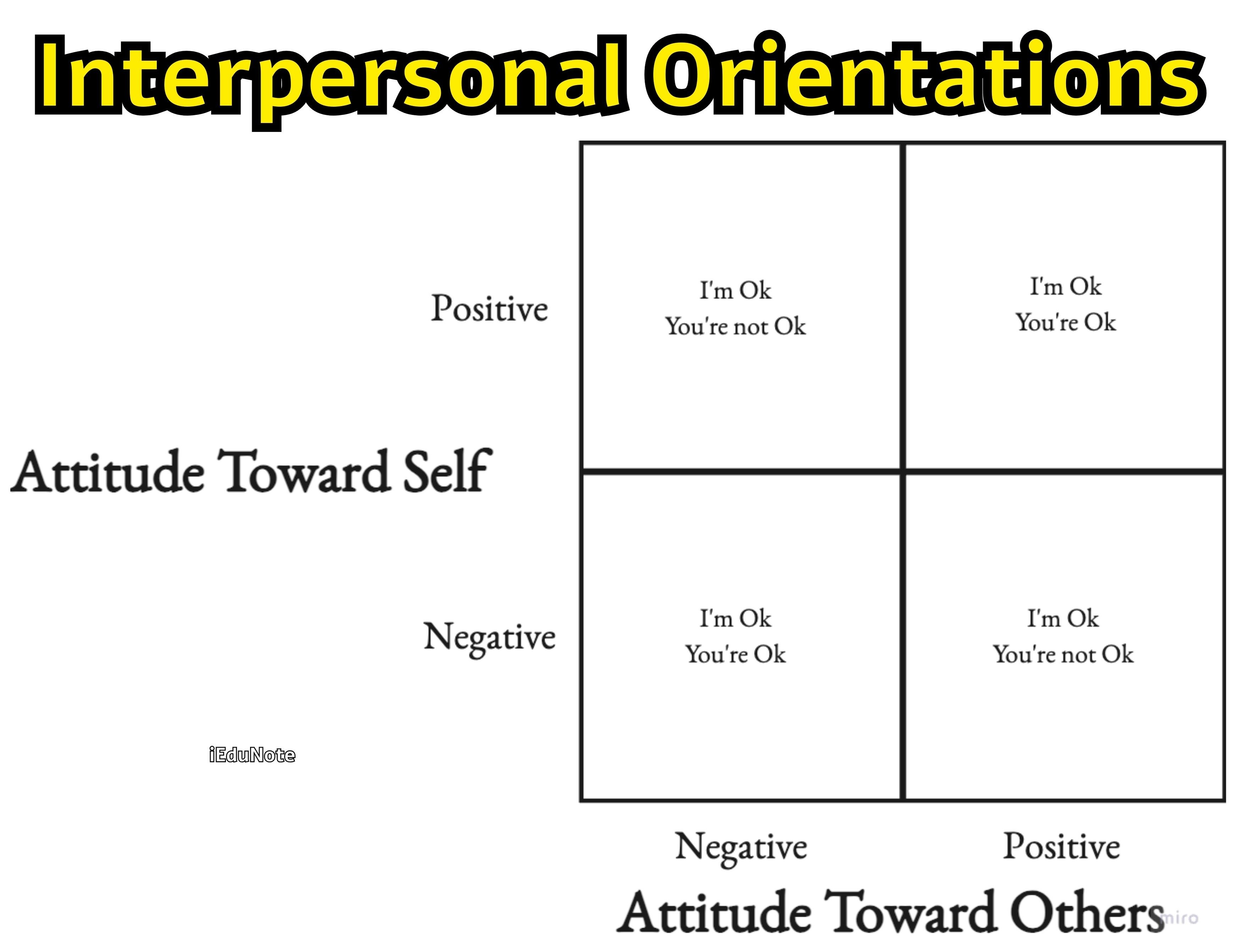

Interpersonal Orientations

Each person tends to exhibit one of four interpersonal orientations, i.e., dominating people. That philosophy tends to remain with the person for a lifetime unless major experiences occur to change it. Although one orientation tends to dominate a person’s transactions, other orientations may be exhibited from time to time in specific transactions. That is, one orientation dominates, but it is not the only position ever taken.

Interpersonal orientations stem from a combination of two viewpoints. First, how do people view themselves? Second, how do they view other people in general?

he combination of either a positive response (OK) or a negative response (not OK) to each question results in four possible interpersonal orientations.

The desirable perspective and the one that involves the greatest likelihood of healthy interactions is “I’m OK — You’re OK.” It shows healthy acceptance of self and respect for others.

It will most likely lead to constructive communications, productive conflict, and mutually satisfying confrontations.

The important point is that the “I’m OK — You’re OK” perspective can be learned regardless of one’s present interpersonal orientation. Therein lies society’s hope for improved interpersonal transactions.

Stroking

People seek stroking in their interactions with others. Stroking is defined as any act of recognition for another. It applies to all types of recognition, such as physical, verbal, and nonverbal contact between people.

In most jobs, the primary stroking method is verbal, such as “Pedro, you had an excellent sales record last month.” Physical strokes include a pat on the back and a firm handshake.

Strokes may be either positive, negative, or mixed. Positive strokes feel good when they are received and contribute to the recipient’s sense of being OK. Negative strokes hurt physically or emotionally and make the recipient feel less OK about themselves.

An example of a mixed stroke is this supervisor’s comment: “Oscar, that’s a good advertising layout, considering the small amount of experience you have in this field.”

There is also a difference between conditional and unconditional strokes. Conditional strokes are offered to employees if they perform correctly or avoid problems.

For example, a sales manager may promise an employee that “I will give you a raise if you sell three more insurance policies.” Unconditional strokes are presented without any connection to behavior.

Although they may make a person feel good (e.g., “You’re a fine employee”), they may also confuse employees because they do not indicate how more strokes may be earned.

Supervisors will get better results if they give more strokes in a behavior modification framework, where the reward is contingent upon the desired activity. Employee hunger for strokes and the occasional reluctance of supervisors to use them is demonstrated in this conversation:

Melissa, a stockbroker, had made a presentation to a group of prospective customers. Later, she excitedly asked her manager how she had done. “You did a nice job,” he began (and Melissa’s eyes lit up in pleasure), “not a great job, but a nice job.” Although she didn’t show her disappointment, we can guess that his qualified remark considerably dampened her spirits.

Applications to Conflict Resolution: There are several natural connections between assertiveness, interpersonal orientation, and the approaches to resolving conflict discussed earlier in this chapter. The “I’m OK — You’re OK” person is likelier to seek a win-win outcome, applying assertiveness and a confrontational strategy.

Other probable connections are shown in the figure. Once more, the relationship among several behavioral ideas and actions is apparent.

Assertiveness training and combining stroking can be powerful tools for increasing interpersonal effectiveness. They both share the goal of helping employees feel OK about themselves and others. The result is that they help improve communication and interpersonal cooperation.

Although individuals can practice them, these tools will be most effective when they are widely used throughout the organization and supported by top management.

Together, they form an important foundation for the more complex challenges that confront people who work in small groups and committees.