The Italian Niccolo Machiavelli is heralded as the founding father of political ethics. He believed that a political leader might be required to commit acts that would be wrong if done privately.

In contemporary democracies, this idea has been reframed as the problem of dirty hands, described most influentially by Michael Walzer, who argues that the problem creates a paradox: the politician must sometimes do “wrong to do right.” The politician uses violence to prevent greater violence, but his act is still wrong, even if justified.

Dennis Thompson has argued that in a democracy, citizens should hold the leader responsible, and therefore if the act is justified, their hands are dirty too. He also shows that in large political organizations, it is often not possible to tell who is actually responsible for the outcomes, a problem known as the problem of many hands.

Political ethics not only permits leaders to do things that would be wrong in private life but also requires them to meet higher standards than would be necessary for private life.

They may, for example, have less of a right to privacy than do ordinary citizens and no right to use their office for personal profit. The major issues here concern conflict of interest. We conclude our discussion of politics by providing some ethical guidelines for political behavior.

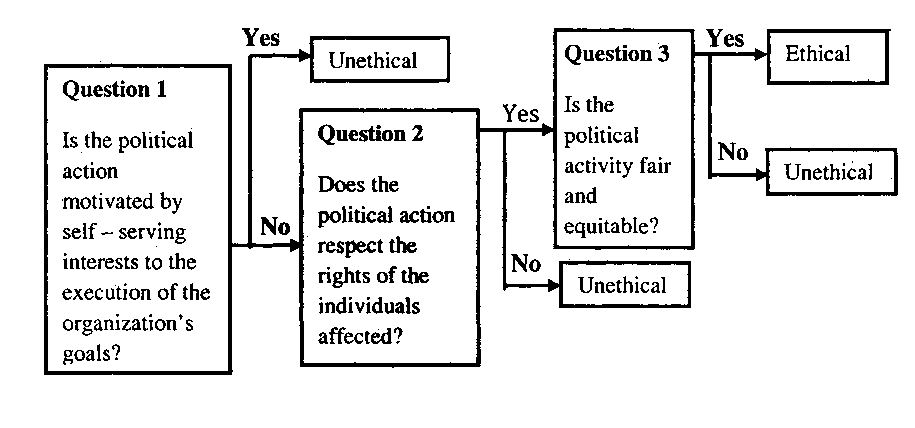

Although there are no – clear-cut ways to differentiate ethical from unethical politicking, there are some questions you should consider.

This tree is built on the three ethical decision criteria:

- Utilitarianism

- Rights.

- Justice

The first question you need to answer addresses self-interest versus organizational goals.

Ethical actions are consistent with the organization’s goals. Spreading untrue rumors about the safety of a new product introduced by your company in order to make that product’s design team look bad is unethical.

However, there may be nothing unethical if a department head exchanges favor with her/his division’s purchasing manager in order to get a critical contract processed quickly.

The second question concerns the rights of other parties.

The final question that needs to be addressed relates to whether the political activity conforms to standards of equity and justice. The department head who inflates the performance evaluation of favored employees and deflates the evaluation of a disfavored employee – and then uses these evaluations to justify giving the former a big raise and nothing to the latter – has treated the disfavored employee unfairly.

Unfortunately, the answers to the questions in Figure are often argued in ways to make unethical practices seem ethical. Powerful people, for example, can become very good at explaining self-serving behaviors in terms of the organization’s best interests.

Similarly, they can persuasively argue that unfair actions are really fair and just. Our point is that immoral people can justify almost any behavior. Those who are powerful, articulate, and persuasive are most vulnerable because they are likely to be able to get away with unethical practices successfully.

When faced with an ethical dilemma regarding organizational politics, try to answer the questions in Figure truthfully. If you have a strong power base, recognize the ability of power to corrupt.

Remember, it’s a lot easier for the powerless to act ethically if for no other reason than they typically have very little political discretion to exploit.