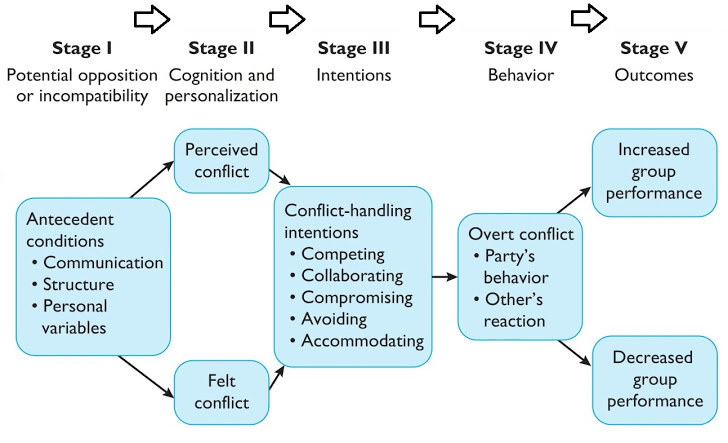

Organizational conflict arises when the goals, interests, or values of different individuals or groups are incompatible, and those individuals or groups block or thwart one another’s attempts to achieve their objectives. The conflict Process shows how conflict works within the organization.

We can identify the stages of a conflict that is born and grows in an organization. In this post, we will look at the stages of a conflict, covering its birth, rise, and ending in it.

5 Stages/Levels/Steps Conflict Process are;

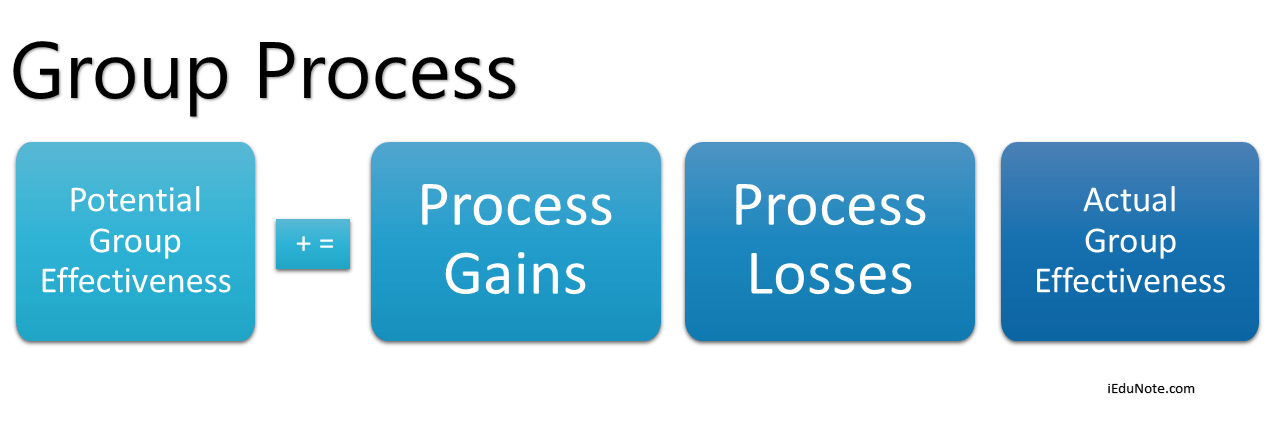

The conflict process consists of five stages that show how conflict begins, grows, and unfolds among individuals or groups with different goals, interests, or values of the organization.

These stages are described below;

Stage 1: Potential Opposition or Incompatibility

The first step in the conflict process is the presence of conditions that create opportunities for conflict to develop. These cause or create opportunities for organizational conflict to arise.

They need not lead directly to conflict; one of these conditions is necessary if the conflict is to surface.

For simplicity’s sake, these conditions have been condensed into three general categories.

- Communication,

- Structure, and

- Personal Variables.

These 3 conditions cause conflict are explained;

1. Communications

Different word connotations, jargon, insufficient exchange of information, and noise in the communication channel are all antecedent conditions to conflict.

Too much communication, as well as too little communication, can lay the foundation for conflict.

Example of Communications:

Susan had worked in purchasing at Abir Corporation for three years. She enjoyed her work, in large part, because her boss, Hasan, was a great guy to work for. Then Hasan got promoted six months ago, and Chuck took his place. Susan says her job is a lot more frustrating now.

“Hasan and I were on the same wavelength. It’s not that way with Chuck. He tells me something, and I do it. Then he tells me I did it wrong. I think he means one thing but says something else. It’s been like this since the day he arrived. I don’t think a day goes by when he isn’t yelling at me for something. You know, there are some people you just find it easy to communicate with. Well, Chuck isn’t one of those!”

Susan’s comments illustrate that communication can be a source of conflict. It represents those opposing forces that arise from semantic difficulties, misunderstandings, and “noise” in the communication channels. Much of this discussion can be related back to our comments on communication.

A review of the research suggests that differing word connotations, jargon, insufficient exchange of information, and noise in the communication channel are all barriers to communication and potential antecedent conditions to conflict.

Evidence demonstrates that semantic difficulties arise as a result of differences in training, selective perception, and inadequate information about others.

Research has further demonstrated a surprising finding: the potential for conflict increases when either too little or too much communication takes place.

Apparently, an increase in communication is functional up to a point whereupon it is possible to overcommunicate, with a resultant increase in the potential for conflict.

Too much information as well as too little, can lay the foundation for conflict.

Furthermore, the channel chosen for communicating can have an influence on stimulating opposition. The filtering process that occurs as information is passed among members and the divergence of communications from format or previously established channels offer potential opportunities for conflict to arise.

2. Structure

In this context, the term structure includes variables such as size, the degree of specialization in the tasks assigned to group members, jurisdictional clarity, members/goal compatibility, leadership styles, reward systems, and the degree of dependence between groups.

The size and specialization act as forces to stimulate conflict. The larger the group and the more specialized its activities, the greater the likelihood of conflict. Tenure and conflict are inversely related.

The potential for conflicts tends to be greatest when group members are younger and when turnover is high.

In defining where responsibility for action lies, the greater the ambiguity, the greater the potential for conflict. Such Jurisdictional ambiguity increases inter-group fighting for control or resources and territory.

Example of Structures:

Sumana and Afsana both work at the Portland Furniture Mart, a large discount furniture retailer. Sumana is a salesperson on the floor; Afsana is the company credit manager.

The two women have known each other for years and have much in common—they live within two blocks of each other, and their oldest daughters attend the same middle school and are best friends.

In reality, if Sumana and Afsana had different jobs, they might be best friends themselves, but these two women are consistently fighting battles with each other. Sumana’s job is to sell furniture, and she does a heck of a job. But most of her sales are made on credit.

Because Afsana’s job is to make sure the company minimizes credit losses, she regularly has to turn down the credit application of a customer to whom Sumana has just closed a sale. It’s nothing personal between Sumana and Afsana—the requirements of their jobs just bring them into conflict.

The conflicts between Sumana and Afsana are structural in nature. The term structure is used, in this context, to include variables such as size, degree of specialization in the tasks assigned to group members, jurisdictional clarity, member-goal compatibility, leadership styles, reward systems, and the degree of dependence between groups.

Research indicates that size and specialization act as forces to stimulate conflict. The larger the group and the more specialized its activities, the greater the likelihood of conflict. Tenure and conflict have been found to be inversely related. The potential for conflict tends to be the greatest when group members are younger and turnover is high.

The greater the ambiguity in precisely defining where responsibility for actions lies, the greater the potential for conflict to emerge. Such jurisdictional ambiguities increase intergroup fighting for control of resources and territory.

Groups within organizations have diverse goals. For instance, purchasing is concerned with the timely acquisition of inputs at low prices, marketing’s goals concentrate on disposing of outputs and increasing revenues, quality control’s attention is focused on improving quality and ensuring that the organization’s products meet standards, and production units seek efficiency of operations by maintaining a steady production flow. This diversity of goals among groups is a major source of conflict.

When groups within an organization seek diverse ends, some of which—such as sales and credit at Portland Furniture Mart—are inherently at odds, there are increased opportunities for conflict.

There is more indication that a close style of leadership—tight and continuous observation with general control of others’ behaviors—increases conflict potential, but the evidence is not particularly strong. Too much reliance on participation may also stimulate conflict.

Research tends to confirm that participation and conflict are highly correlated, apparently because participation encourages the promotion of differences. Reward systems, too, are found to create conflict when one member’s gain is at another’s expense.

Finally, if a group is dependent on another group (in contrast to the two being mutually independent) or if interdependence allows one group to gain at another’s expense, opposing forces are stimulated.

3. Personal Variables

Certain personality types- for example, highly authoritarian and dogmatic individuals- lead to potential conflict. Another reason for the conflict is the difference in value systems.

Value differences are the best explanations of diverse issues, such as prejudice disagreements over one’s contribution to the group and the rewards one deserves.

Example of Personal Variables:

Did you ever meet individuals to whom you took an immediate disliking? Most of the opinions they expressed, you disagreed with.

Even insignificant characteristics—the sound of their voice, the smirk when they smiled, their personality—annoyed you. We’ve all met people like that. When you have to work with such individuals, there is often the potential for conflict.

Our last category of potential sources of conflict is personal variables. They include the individual value systems that each person has and the personality characteristics that account for individual idiosyncrasies and differences.

Stage 2: Cognition and Personalization

The parties must perceive conflict to it; whether or not the conflict exists is a perception issue, the second step of the Conflict Process.

If no one is aware of a conflict, then it is generally agreed that no conflict exists. Because competition is perceived does not mean that it is personalized.

For example; a may be aware that B and A are in serious disagreements, but it may not make A tense or nations, and it may have no effect whatsoever on A’s affection towards B.

It is the felt level when individuals become emotionally involved that parties experience anxiety, tension, or hostility.

Stage 2 is the place in the process where the parties decide what the conflict is about, and emotions play a major role in shaping perception.

If the conditions cited in Stage I negatively affect something that one party cares about, then the potential for opposition or incompatibility becomes actualized in the second stage. The antecedent conditions can only lead to conflict when one or more of the parties are affected by, and aware of, the conflict.

As we noted in our definition of conflict, perception is required. Therefore, one or more of the parties must be aware of the existence of the antecedent conditions.

However, just because a conflict is perceived does not mean that it is personalized. In other words, “B may be aware that A and C are in serious disagreement… but it may not make B tense or anxious, and it may not affect A’s affection toward B. It is at the felt level, when individuals become emotionally involved, that they experience anxiety, tension, frustration, or hostility.

Keep in mind two points. First, Stage II is important because it’s where conflict issues tend to be defined. This is the place in the process where the parties decide what the conflict is about.

And in turn, this “sense-making” is critical because the way a conflict is defined goes a long way toward establishing the sort of outcomes that might settle it.

For instance, if I define our salary disagreement as a zero-sum situation—that is, if you get the increase in pay you want, there will be just that amount less for me—-I am going to be far less willing to compromise than if I frame the conflict as a potential win-win situation (i.e., the dollars in the salary pool might be increased so that both of us could get the added pay we want).

So, the definition of a conflict is important, for it typically delineates the set of possible settlements.

Secondly, emotions play a major role in shaping perceptions.

For example, negative emotions have been found to produce oversimplification of issues, reductions in trust, and negative interpretations of the other party’s behavior.

In contrast, positive feelings have been found to increase the tendency to see potential relationships among the elements of a problem, to take a broader view of the situation, and to develop more innovative solutions.

Stage 3: Intentions

Intentions are decisions to act in a given way; intentions intervene between people’s perceptions and emotions and their overt behavior.

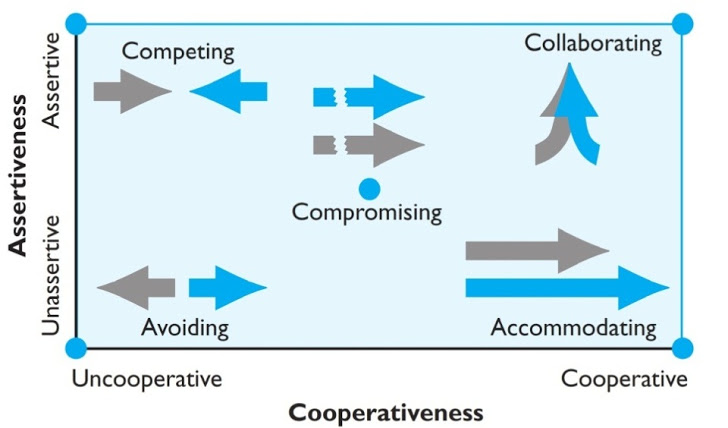

Using two dimensions, cooperativeness (the degree to which one party attempts to satisfy the other party’s concerns) and assertiveness (the degree to which one party attempts to satisfy his or her concerns), five conflict-handling intentions can be identified.

Intentions intervene between people’s perceptions and emotions and their overt behavior. These intentions are decisions to act in a given way.

Why are intentions separated out as a distinct stage? You have to infer the other’s intent to know how to respond to that other’s behavior.

Many conflicts are escalated merely by one party attributing the wrong intentions to the other party. Additionally, there is typically a great deal of slippage between intentions and behavior, so behavior does not always accurately reflect a person’s intentions.

5 Conflict-Handling Intention

There are five conflict-handling intentions;

- Competing (I Win, You Lose),

- Collaborating (I Win, You Win),

- Avoiding (No Winners, No Losers),

- Accommodating (I lose, You win), and

- Compromising (You Bend, I Bend).

These are also known as conflict-handling styles and orientations, which are discussed below:

1. Competing (I Win, You Lose)

When one seeks to satisfy his or her interests regardless of the impact on the other parties to the conflict, he or she is competing.

The competition involves authoritative and assertive behaviors.

In this style, the aggressive individual aims to instill pressure on the other parties to achieve a goal. It includes the use of whatever means to attain what the individual thinks is right.

It may be appropriate in some situations, but it shouldn’t come to a point where the aggressor becomes too unreasonable.

Dealing with conflict with an open mind is vital for a resolution to be met.

When one person seeks to satisfy his or her own interests, regardless of the impact on the other parties to the conflict, he or she is competing. Examples include intending to achieve your goal at the sacrifice of the other’s goal, attempting to convince another that your conclusion is correct and his or hers is mistaken, and trying to make someone else accept blame for a problem.

2. Collaborating (I Win, You Win)

When each party to conflict desires to fully satisfy the concerns of all parties, we have cooperation and the search for a mutually beneficial outcome. In collaborating, the intention of the parties is to solve the problem by clarifying differences rather than by accommodating various points of view. Examples include attempting to find a win-win solution that allows both parties’ goals to be completely achieved and seeking a conclusion that incorporates the valid insights of both parties.

A situation in which the parties to conflict each desire to satisfy the concerns of all the parties fully.

In collaborating, the parties intend to solve the problem by clarifying differences rather than accommodating various viewpoints.

Collaborating aims to find a solution to the conflict by cooperating with other parties involved.

Hence, communication is an important part of this strategy.

In this mechanism, the effort is exerted in digging into the issue to identify the needs of the individuals concerned without removing their respective interests from the picture.

Collaborating individuals aim to come up with a successful resolution creatively without compromising their satisfaction.

3. Avoiding (No Winners, No Losers)

A person may recognize that a conflict exists and want to withdraw from it or suppress it. Examples of avoiding include trying to just ignore a conflict and avoiding others with whom you disagree.

A person may recognize that a conflict exists and want to withdraw from it or suppress it. Avoiding included trying to just ignore a conflict and avoiding others with whom you disagree.

In this approach, there is withdrawal from the conflict. The problem is being dealt with through a passive attitude.

Avoiding is mostly used when the perceived negative end outweighs the positive outcome.

In employing this, individuals end up ignoring the problem, thinking that the conflict will resolve itself. It might be applicable in certain situations but not in all.

Avoidance would mean that you neglect the responsibility that comes with it.

The other individuals involved might think that you are neglecting the problem. Thus, it is better to confront the problem before it gets worse.

4. Accommodating (I lose, You win)

When one party seeks to appease an opponent, that party may be willing to place the opponent’s interests above his or her own. In other words, in order for the relationship to be maintained, one party is willing to be self-sacrificing. We refer to this intention as accommodating.

Examples are a willingness to sacrifice your goal so the other party’s goal can be attained, supporting someone else’s opinion despite your reservations about it, and forgiving someone for an infraction and allowing subsequent ones.

The willingness of one partying a conflict to place the opponent’s interest above his or her own.

Accommodation involves having to deal with the problem with an element of self-sacrifice; an individual sets aside his concerns to maintain peace in the situation.

Thus, the person yields to what the other wants, displaying a form of selflessness.

It might come as an immediate solution to the issue; however, it also brings about a false manner of dealing with the problem.

This can be disruptive if there is a need to come up with a more sound and creative way out of the problem. This behavior will be most efficient if the individual is in the wrong, as it can come as a form of conciliation.

5. Compromising (You Bend, I Bend)

A situation in which each party to a conflict is willing to give up something.

Intentions provide general guidelines for parties in a conflict situation. They define each party’s purpose.

Yet people’s intention is not fixed. During the conflict, they might change because of re-conceptualization or because of an emotional reaction to the behavior of another party.

Compromising is about coming up with a resolution that would be acceptable to the parties involved.

Thus, one party is willing to sacrifice their own sets of goals as long as the others will do the same.

Hence, it can be viewed as a mutual give-and-take scenario where the parties submit the same amount of investment for the problem to be solved.

A disadvantage of this strategy is the fact that since these parties find an easy way around the problem, the possibility of coming up with more creative ways for a solution would be neglected.

When each party to the conflict seeks to give up something, sharing occurs, resulting in a compromised outcome. In compromising, there is no clear winner or loser.

Rather, there is a willingness to ration the object of the conflict and accept a solution that provides incomplete satisfaction of both parties’ concerns.

The distinguishing characteristic of compromising, therefore, is that each party intends to give up something. Examples might be a willingness to accept a raise of $1 an hour rather than $2, to acknowledge partial agreement with a specific viewpoint, and to take partial blame for an infraction.

Intentions provide general guidelines for parties in a conflict situation. They define each party’s purpose. Yet, people’s intentions are not fixed. During a conflict, they might change because of reconceptualization or because of an emotional reaction to the other party’s behavior.

However, research indicates that people have an underlying disposition to handle conflicts in certain ways.

Specifically, individuals have preferences among the five conflict-handling intentions just described. These preferences tend to be relied upon quite consistently, and a person’s intentions can be predicted rather well from a combination of intellectual and personality characteristics.

So, it may be more appropriate to view the five conflict-handling intentions as relatively fixed rather than as a set of options from which individuals choose to fit an appropriate situation.

That is when confronting a conflict situation, some want to run away, others want to be obliging, and still others want to “split the difference.”

When to use the Five Conflict-Handling Orientations

5 conflict-handling orientations are not universally applicable. Its uses vary from time to time, person to person, and even situation to situation.

When it uses appropriate are given below:

| Conflict- Handling Orientation | Best Scenario to Use Conflict- Handling Orientation |

| Competition |

|

| Collaboration |

|

| Avoidance |

|

| Accommodation |

|

| Compromise |

|

Stage 4: Behavior

This is a stage where conflict becomes visible. The behavior stage includes the statements, actions, and reactions made by the conflicting parties.

These conflict behaviors are usually overt attempts to implement each party’s intentions.

When most people think of conflict situations, they tend to focus on Stage 4.

Why?

Because this is a stage Where conflict becomes visible. The behavior stage includes the statements, actions, and reactions made by the conflicting parties;

These conflict behaviors are usually overt attempts to implement each party’s intentions. But these behaviors have a stimulus quality that is separate from intentions.

As a result of miscalculations or unskilled enactments, overt behaviors sometimes deviate from original intentions.

It helps to think of stage 4 as a dynamic process of interaction.

Conflict Resolution Techniques

| Problem solving | Face-to-face meeting of the conflicting parties for the purpose of identifying the problem and resolving it through open discussion. |

| Superordinate goals | Creating a shared goal that cannot be attained without the cooperation of each of the conflicting parties. |

| Expansion of resources | When a conflict is caused by the scarcity of a resource—say, money, promotion, opportunities, office space—expansion of the resource can create a win-win solution. |

| Avoidance | Withdrawal from, or suppression of, the conflict. |

| Smoothing | Playing down differences while emphasizing common interests between the conflicting parties. |

| Compromise | Each party to the conflict gives up something of value. |

| Authoritative command | Management uses its formal authority to resolve the conflict and then communicates its desires to the parties involved. |

| Altering the human variable | Using behavioral change techniques such as human relations training to alter attitudes and behaviors that cause conflict. |

| Altering the structural variables | Changing the formal organization structure and the interaction patterns of conflicting parties through job redesign, transfers, creation of coordinating positions, and the like. |

| Communication | Using ambiguous or threatening messages to increase conflict levels. |

| Bringing in outsiders | Adding employees to a group whose backgrounds, values, attitudes, or managerial styles differ from those of present members. |

| Restructuring the organization | Realigning work groups, altering rules and regulations, increasing inter-dependence, and making similar structural changes to disrupt the status quo. |

| Appointing a devil’s advocate | Designating a critic to purposely argue against the majority positions held by the group. |

| Communication | Using ambiguous or threatening messages to increase conflict levels. |

| Bringing in outsiders | Adding employees to a group whose backgrounds, values, attitudes, or managerial styles differ from those of present members. |

| Restructuring the organization | Realigning work groups, altering rules and regulations, increasing inter-dependence, and making similar structural changes to disrupt the status quo. |

| Appointing a devil’s advocate | Designating a critic to purposely argue against the majority positions held by the group. |

This lists the major resolution and stimulation techniques that allow managers to control conflict levels. Notice that several of the resolution techniques were earlier described as conflict-handling intentions. This, of course, shouldn’

When most people think of conflict situations, they focus on Stage 4. Why? Because this is where conflicts become visible. The behavior stage includes the conflicting parties’ statements, actions, and reactions.

These conflict behaviors are usually overt attempts to implement each party’s intentions. However these behaviors have a stimulus quality that is separate from intentions. As a result of miscalculations or unskilled enactments, overt behaviors sometimes deviate from original intentions.

It helps to think of Stage IV as a dynamic process of interaction. For example, you make a demand on me; I respond by arguing; you threaten back, and so on.

All conflicts exist somewhere along this continuum. At the lower part of the continuum, we have conflicts characterized by subtle, indirect, and highly controlled forms of tension. An illustration might be a student questioning in class a point the instructor has just made.

Conflict intensities escalate as they move upward along the continuum until they become highly destructive. Strikes, riots, and wars clearly fall in this upper range.

For the most part, you should assume that conflicts that reach the upper ranges of the continuum are almost always dysfunctional. Functional conflicts are typically confined to the lower range of the continuum.

If a conflict is dysfunctional, what can the parties do to de-escalate it? Or, conversely, what options exist if conflict is too low and needs to be increased? This brings us to conflict resolution techniques.

Stage 5: Outcomes

The action-reaction interplay between the conflicting parties results in consequences.

These outcomes may be functional in that the conflict improves the group’s performance or dysfunctional in that it hinders group performance.

Conflict is constructive when it improves the quality of decisions, stimulates creativity and innovations, and encourages interest and curiosity among group members to provide the medium through which problems can be aired. Tensions released and foster an environment of self-evaluation and change.

Conflict is dysfunctional when uncontrolled opposition breeds discontent, which acts to dissolve common ties and eventually leads to the destruction of the group.

Among the more undesirable consequences are a retarding of communication, reductions in group cohesiveness, and subordination of group goals to the primacy of infighting between members.

The action-reaction interplay between the conflicting parties results in consequences. As our model demonstrates, these outcomes may be functional in that the conflict results in an improvement in the group’s performance or dysfunctional in that it hinders group performance.

Functional Outcomes

How might conflict act as a force to increase group performance? It is hard to visualize a situation in which open or violent aggression could be functional.

However there are a number of instances in which it is possible to envision how low or moderate levels of conflict could improve the effectiveness of a group.

Because people often find it difficult to think of instances in which conflict can be constructive, let’s consider some examples and then review the research evidence. Note how all these examples focus on task and process conflicts and exclude the relationship variety.

Conflict is constructive when it improves the quality of decisions, stimulates creativity and innovation, encourages interest and curiosity among group members, provides the medium through which problems can be aired and tensions released, and fosters an environment of self-evaluation and change.

The evidence suggests that conflict can improve the quality of decision-making by allowing all points, particularly the ones that are unusual or held by a minority, to be weighed in important decisions.

Conflict is an antidote for groupthink. It doesn’t allow the group passively to “rubber-stamp” decisions that may be based on weak assumptions, inadequate consideration of relevant alternatives, or other debilities.

Conflict challenges the status quo and, therefore, furthers the creation of new ideas, promotes reassessment of group goals and activities, and increases the probability that the group will respond to change.

For an example of a company that has suffered because it had too little functional conflict, you don’t have to look further than automobile giant General Motors.

Many of GM’s problems over the past three decades can be traced to a lack of functional conflict. It hired and promoted individuals who were “yes men,” loyal to GM to the point of never questioning company actions.

Managers were, for the most part, conservative white Anglo-Saxon males raised in the midwestern United States who resisted change.

They preferred looking back to past successes rather than forward to new challenges. They were almost sanctimonious in their belief that what had worked in the past would continue to work in the future.

Moreover, by sheltering executives in the company’s Detroit offices and encouraging them to socialize with others inside the GM ranks, the company further insulated managers from conflicting perspectives.

Research studies in diverse settings confirm the functionality of conflict. Consider the following findings.

The comparison of six major decisions made during the administration of four different U.S. presidents found that conflict reduced the chance that groupthink would overpower policy decisions.

The comparisons demonstrated that conformity among presidential advisors was related to poor decision-making, while an atmosphere of constructive conflict and critical thinking surrounded the well-developed decisions. There is evidence indicating that conflict can also be positively related to productivity.

For instance, it was demonstrated that, among established groups, performance tended to improve more when there was conflict among members than when there was fairly close agreement.

The investigators observed that when groups analyzed decisions that had been made by the individual members of that group, the average improvement among the high-conflict groups was 73 percent greater than that of those groups characterized by low-conflict conditions.

Others have found similar results: Groups composed of members with different interests tend to produce higher-quality solutions to a variety of problems than do homogeneous groups.

The preceding discussion leads us to predict that the increasing cultural diversity of the workforce should provide benefits to organizations. And that’s what the evidence indicates.

Research demonstrates that heterogeneity among group and organization members can increase creativity, improve the quality of decisions, and facilitate change by enhancing member flexibility.

For example, researchers compared decision-making groups composed of all Anglo individuals with groups that also contained members from Asian, Hispanic, and black ethnic groups.

The ethnically diverse groups produced more effective and more feasible ideas, and the unique ideas they generated tended to be of higher quality than the unique ideas produced by the all-Anglo group.

Similarly, studies of professionals—systems analysts and research and development scientists—support the constructive value of conflict. An investigation of 22 teams of systems analysts found that the more incompatible groups were likely to be more productive.

Research and development scientists have been found to be most productive when there is a certain amount of intellectual conflict.

Dysfunctional Outcomes

The destructive consequences of conflict on a group or organization’s performance are generally well-known.

A reasonable summary might state that uncontrolled opposition breeds discontent, which acts to dissolve common ties and eventually leads to the destruction of the group.

And, of course, there is a substantial body of literature to document how conflict—the dysfunctional varieties—can reduce group effectiveness.

Among the more undesirable consequences are a retarding of communication, reductions in group cohesiveness, and subordination of group goals to the primacy of infighting between members. At the extreme, conflict can bring group functioning to a halt and potentially threaten the group’s survival.

The demise of an organization as a result of too much conflict isn’t as unusual as it might first appear. For instance, one of New York’s best-known law firms, Shea & Gould, closed down solely because the 80 partners just couldn’t get along.

As one legal consultant familiar with the organization said: “This was a firm that had basic differences among the partners that were basically irreconcilable.” That same consultant also addressed the partners at their last meeting: “You don’t have an economic problem,” he said, “You have a personality problem. You hate each other!”

Creating Functional Conflict

We briefly mentioned conflict stimulation as part of Stage IV of the conflict process. Since the topic of conflict stimulation is relatively new and somewhat controversial, you might be wondering:

If managers accept the interactionist view toward conflict, what can they do to encourage functional conflict in their organizations?

There seems to be general agreement that creating functional conflict is a tough job, particularly in large American corporations. As one consultant put it, “A high proportion of people who get to the top are conflict avoiders.

They don’t like hearing negatives, they don’t like saying or thinking negative things. They frequently make it up the ladder in part because they don’t irritate people on the way up.”

Another suggests that at least seven out of ten people in American business hush up when their opinions are at odds with those of their superiors, allowing bosses to make mistakes even when they know better.

Such anti-conflict cultures may have been tolerable in the past but not in today’s fiercely competitive global economy. Those organizations that don’t encourage and support dissent may find their survival threatened. Let’s look at a couple of approaches organizations are using to encourage their people to challenge the system and develop fresh ideas.

Hewlett-Packard rewards dissenters by recognizing go-against-the-grain types, or people who stay with the ideas. Miller Inc., an office-furniture manufacturer, has a formal system in which employees evaluate and criticize their bosses.

IBM also has a formal system that encourages dissension. Employees can question their boss with impunity. If the disagreement can’t be resolved, the system provides a third party for counsel.

Royal Dutch Shell Group, General Electric, and Anheuser-Busch build devil’s advocates into the decision process.

For instance, when the policy committee at Anheuser-Busch considers a major move, such as getting into or out of a business or making a major capital expenditure, it often assigns teams to make the case for each side of the question. This process frequently results in decisions and alternatives that previously hadn’t been considered.

One common ingredient in organizations that successfully create functional conflict is that they reward dissent and punish conflict avoiders.

The president of Innovis Interactive Technologies, for instance, fired a top executive who refused to dissent.

His explanation:

“He was the ultimate yes-man. In this organization, I can’t afford to pay someone to hear my own opinion.” But the real challenge for managers is when they hear news that they don’t want to hear. The news may make their blood boil or their hopes collapse, but they can’t show it. They have to learn to take the bad news without flinching.

No tight-lipped sarcasm, no eyes rolling upward, no gritting of teeth. Rather, managers should ask calm, even-tempered questions: “Can you tell me more about what happened?” “What do you think we ought to do?” A sincere “Thank you for bringing this to my attention” will probably reduce the likelihood that managers will be cut off from similar communications in the future.